|

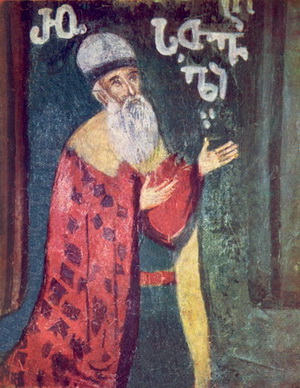

Fresco of Shota Rustaveli in the Monastery of the Cross, an Eastern Orthodox monastery near the Nayot neighborhood of Jerusalem, Israel |

The Knight in the Tiger Skin |

|

Fresco of Shota Rustaveli in the Monastery of the Cross, an Eastern Orthodox monastery near the Nayot neighborhood of Jerusalem, Israel |

Classical literature Iakob Tsurtaveli (V AD) Shota Rustaveli (1172 - 1216) Alexander Chavchavadze (1786 - 1846) Grigol Orbeliani (1804 - 1883) Nikoloz Baratashvili (1817 - 1844) Raphael Eristavi (1824 - 1901) Ilia Chavchavadze (1837 - 1907) Akaki Tsereteli (1840 - 1915) Vazha Pshavela (Luka Razikashvili) (1861 - 1915) David Kldiashvili (1862 - 1931) Galagtion Tabidze (1892 - 1959) Irakli Abashidze (1909 - 1992) Zviad Gamsakhurdia (1939 - 1993) Contemporary literature Dato Barbakadze Irakli Kakabadze |

Marine Tsiklauri - The Aspects of Civic Consciousness in Georgian Literature

Nino Popiashvili - Woman writer – Georgian literary experience

Elguja Khintibidze - Georgian Literature in European Scholarship

Early Georgian literature was influenced by two distinctive civilizations-medieval Eastern Orthodox Christianity and the civilization of Persia. From the 6th to the 10th cent. the literature, produced primarily in monasteries, was ecclesiastical; translations of the Bible were the principal works. From the end of the 11th cent. to the early 13th cent., classical old Georgian poetry, secular in nature and strongly influenced by the Persian epic, enjoyed its greatest flowering. The masterpiece of this period was the epic poem by Shota Rustaveli, The Man in the Panther's Skin (tr. 1912). Nationalistic in feeling, it is distinguished by a remarkable metrical pattern of fluent rhymes and subtle alliterations. In this same period, the poet Chakrudkhadze wrote 20 odes, titled Tamariani, and Ioane Shavteli completed Abdul Messiah.

After the 13th cent. Mongol invasion there was little important literature over the next few centuries.

In the 17th cent., King Teimuraz I and King Archil Sulkhan contributed extensively to the evolution of Georgia's modern prose, and Saba Orbelian wrote the outstanding Book of Wisdom and Lies.

In the 18th cent. the foremost writers were David Guramishvili, author of The Woes of Kartli, and the lyric poet Bessarion Gabashvili. Throughout these years troubadour literature also evolved.

In the 19th cent., romanticism was the dominant style, as seen in the writings of Alexander Chavchavadze, Nikoloz Baratashvili, and Grigol Orbeliani. The outstanding representatives of classical Georgian poetry were Ilia Chavchavadze and Alaki Tsereteli.

In the early 20th cent., A. Abashili and S. Shanshiashvili were the leading writers of the pre-Soviet period. Major Georgian literary figures, including the poets Paolo Iashvili and Titsian Tabidze and the novelist Mikheil Javakhishvili, were victims of Stalin's purges. In the post-Stalin period, Georgian writers such as the novelist Konstantine Gamsakhurdia, the playwright Shalva Dadiani, and the poet Ioseb Grishashvili, reflected Soviet literary trends, styles, and topics.

More recent writing, such as the novels of Nodor Dumbadze and the poems of Ana Kalandadze, has emphasized nationalist themes anticipating national independence.

Origins and early development

The origins of Georgian literature date to the 4th century, when the Georgian people were converted to Christianity and a Georgian alphabet was developed. The emergence of a rich literary language and an original religious literature was simultaneous with a massive effort to translate texts from Greek, Armenian, and Syriac. Among the earliest works in Georgian is the prose Tsameba tsmidisa Shushanikisi dedoplisa (470 or later; “The Passion of Saint Queen Shushanik”), attributed to Iakob Tsurtaveli. Old Georgian ecclesiastical literature reached its acme in the 10th century with the lyrical hymns composed and collected by Ioane Minchkhi and Mikael Modrekili and with such biographies of the Church Fathers as Tskhovreba Seraapionisi (c. 910; “The Life of Serapion”) by Basil Zarzmeli and Grigol Khandztelis tskhovreba (c. 950; “Grigol of Khandzta”) by Giorgi Merchule. Chronicles—such as Moktseva Kartlisa (c. 950; “The Conversion of Georgia”) and Kartlis tskhovreba (compiled between the 10th and 13th centuries; “The Life of Kartli”)—evolved from legend to genuine historiography.

With the weakening of the Byzantine Empire in the 10th century, Georgia’s rulers achieved prosperity sufficient to allow a secular literature to develop. King David IV (the Builder) and, later, Queen Tamara, his great-granddaughter, oversaw a cultural golden age that reached from the late 11th to the early 13th century. They encouraged and commissioned works in all the arts but particularly in poetry and prose. (They themselves, like most of Georgia’s Bagratid monarchs, were also writers.) Influenced by Persian literature—especially Ferdowsī’s Shāh-nāmeh (“Book of Kings”), an 11th-century epic—Georgian courtly romance and epic flourished. In verse, Georgia acquired its national monument, Shota Rustaveli’s extravagant but sophisticated courtly romance Vepkhvistqaosani (c. 1220; The Knight in the Panther’s Skin). It was preceded and perhaps influenced by Amiran-Darejaniani (probably c. 1050; Eng. trans. Amiran-Darejaniani), a wild prose tale of battling knights, attributed by Rustaveli to Mose Khoneli, who is otherwise unknown.

Georgia’s devastation by Genghis Khan in the 1220s and by Timur in the 1390s resulted in the loss of much of the literature created during the golden age—what survives today is only a fraction of what was written—and effectively ended literary production for two centuries. A renaissance began in the early 17th century with the harrowingly personal, though ornate, poetry of King Teimuraz I; among his works is Tsigni da tsameba Ketevan dedoplisa (“The Book and Passion of Queen Saint Ketevan”), a gruesome account of his mother’s martyrdom written in 1625, soon after her death. Less-inspired authors were content to fabricate sequels to Rustaveli’s The Knight in the Panther’s Skin, but contact with Italian and French missionaries and ambassadors in Tbilisi slowly crystallized into fresh ideas.

The 18th and 19th centuries

In the early 18th century, Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani, supported by his pupil and nephew King Vakhtang VI, introduced modern schooling and printing to Georgia. Orbeliani also compiled the first extant Georgian dictionary and wrote a book of instructive fables, Tsigni sibrdzne-sitsruisa (c. 1700; The Book of Wisdom and Lies). Two major poets emerged in the next generation: Davit Guramishvili used colloquial language to write revealing autobiographical poetry that has a Romantic immediacy, and Besiki (pseudonym of Besarion Gabashvili) adapted conventional poetics to passionate love poetry. Both died in the 1790s while in exile.

During the 18th century, Georgia sought salvation from Ottoman and Persian rule by making an alliance with Russia. In 1801 Russia abolished the Georgian state, dethroned its kings, and made Russian the language of administration. But Russian rule was fairly bloodless and opened routes to European culture. A generation of Georgian Romantic poets was inspired by French and German literature and philosophy. Aleksandre Chavchavadze, father-in-law to Russian playwright Aleksandr Sergeyevich Griboyedov, was an original, contemplative poet; Nikoloz Baratashvili was a visionary genius comparable to the English poet John Keats.

Prose fiction, which could be sustained only by a large educated readership, was slower to develop. By the 1860s, however, fiction and nonfiction prose was flourishing. Ilia Chavchavadze and Akaki Tsereteli had immense moral and intellectual authority and measurable narrative talent, as displayed, for example, in Chavchavadze’s Katsia-adamiani? (1859–63; “Is That a Human Being?”), which attacks the degenerate gentry, and Tsereteli’s fine autobiographical Chemi tavgadasavali (1894–1909; “The Story of My Life”). Aleksandre Qazbegi was the first commercially successful prose writer in Georgia, his melodramatic fiction drawing on the legends and pagan ethos of the Caucasian highlanders.

The development of Georgian theatre, which needed prosperous city dwellers, was stunted during the 19th century. Its sole significant dramatist was Giorgi Eristavi, who edited a literary journal, directed the Georgian-language theatre (which functioned only sporadically until the 1880s), and translated Russian comedies. He wrote one effective drama, Sheshlili (written 1839, first performed 1861; “The Madwoman”), about women in conflict, as well as two successful comedies, Dava, anu tochka da zapetaia (written 1840, first performed 1850; “The Lawsuit, or Semicolon”) and Gaqra (1849; “The Family Settlement”). From the 19th century through the turn of the 21st, Georgian theatre had fine actors and directors but an impoverished repertoire.

The 20th century

Vazha-Pshavela (pseudonym of Luka Razikashvili) is modern Georgia’s greatest genius. His finest works are tragic narrative poems (Stumar-maspindzeli [1893; “Host and Guest”], Gvelis mchameli [1901; “The Snake-Eater”]) that combine Caucasian folk myth with human tragedy. Young Georgian poets and prose writers were subsequently inspired by European Decadence and Russian Symbolism as well as by the highlanders’ folklore that imbues all Vazha-Pshavela’s language, imagery, and outlook. His greatest pupils were the dramatist and novelist Grigol Robakidze and the poet Galaktion Tabidze. Robakidze developed the themes of Vazha-Pshavela’s “The Snake-Eater” in The Snake Skin, a tale of a poet’s search for his real identity. Robakidze also led a group known as the Tsisperqnatslebi (“Blue Horns”); its best poet was Titsian Tabidze, whose work was indebted to Russian poetry. From 1918 to 1921 Georgia was an independent state; despite war and destitution, the period witnessed an explosion of poetry, prose, and “happenings”—anarchistic artistic and political outbursts stimulated by the mixture in Tbilisi of the refugee Russian avant-garde and Georgian poets heady with their liberation.

Invasion by the Soviet Red Army in February 1921 sobered Georgian writers. In the 1920s and ’30s the prose writer Mikheil Javakhishvili—who, having been sentenced to death by Soviet authorities but later released, went on to become a great writer—produced inventive and captivating prose that often tells the story of a sympathetic doomed rogue, as in the novels Kvachi Kvachantiradze da misi tavgadasavali (1924; “Kvachi Kvachantiradze and His Adventures”) and Arsena Marabdeli (1933–36; “Arsena of Marabda”). The most enigmatic Georgian prose writer of the 20th century was Konstantine Gamsakhurdia; like Robakidze, he was influenced by German culture (especially the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche), and in his work he combined the ethos of the Austro-German poet Rainer Maria Rilke with Caucasian folk myth. Befriended by Lavrenty Pavlovich Beria—then Stalin’s satrap in the Caucasus, later the director of the Soviet secret police—Gamsakhurdia was free to write grandiose novels on contemporary, mythological, and historical themes.

Georgian writers were decimated by the Bolsheviks in the 1920s; the Great Purge of the 1930s destroyed the survivors. Even those few who survived the holocaust overseen by Beria lost friends, family, nerve, and inspiration. The post-Stalinist thaw was slower in Georgia than in Russia. Fine lyrical poets achieved great popularity in the 1960s: Ana Kalandadze (who had been a harbinger of literary renewal in the 1940s, when her earliest work was published), Murman Lebanidze, and Mukhran Machavariani. The relative liberalism experienced under Eduard Shevardnadze after his appointment in 1972 as first secretary of the Communist Party in Georgia empowered two important novelists. Chabua Amirejibi continued in the spirit of Javakhishvili’s novels centred on rogues with the magnificent Data Tutashkhia (1972) and the autobiographical Gora Mborgali (1995), while Otar Chiladze, with Gzaze erti katsi midioda (1972–73; “A Man Went Down the Road”) and Qovelman chemman mpovnelman (1976; “Everyone That Findeth Me”), began a series of lengthy atmospheric works that fuse Sumerian and Hellenic myth with the predicaments of a Georgian intellectual.

Independence and beyond

The civil war, economic collapse, and emigration that followed independence in the 1990s crippled Georgian publishing and theatre and created an environment where literature could not flourish. But as the country stabilized in the mid-1990s under Shevardnadze, who had by then become its head of state, destitute writers were able to begin again. Chiladze’s novel Avelum (1995), for example, was a notable account of a Georgian intellectual watching his personal “empire of love” crumble together with the Soviet empire. Georgia’s Rose Revolution of 2003 and the emergence of a relatively well-off middle class enabled publishers and theatres to operate. While the older generation of writers remained active—Chiladze published the novel Godori (“The Basket”) in 2003, and Amirejibi’s Giorgi brtsqinvale (“George the Brilliant”), a historical novel preaching national pride, appeared in 2005—a new generation of prose writers appeared, notably the prolific Aka Morchiladze (pseudonym of Giorgi Akhvlediani). His best work includes Mogzauroba Karabaghshi (1992; “Journey to Karabakh”) and a series of semi-fantastic novels about an archipelago called Madatov that is populated by Georgians. Morchiladze’s work shows Georgian literature’s reorientation in the early 21st century from Russian toward English and American influences. The work (some of it written in English) of playwright Lasha Bughadze also attracted international acclaim. A new generation of poets—including Maia Sarishvili, Rati Amaghlobeli, and Kote Qubaneishvili (Kote Kubaneishvili)—showed an inventiveness and irreverence derived from their working as public performers and participating in international festivals.

Donald Rayfield

About Georgian Literature

A very short introduction

Georgian literature is one of the most ancient and richest in the world. Nowadays, Georgian Literary critics perceive that the first Georgian Literary work is “The Life of Saint Nino” dating back to IV century and which is incorporated in "The Conversion of Kartli”s chronicles (XI century). After reconstructing its prototype and analyzing its ancient layers Georgian researchers have revealed that "The Life of Saint Nino" can be traced back to IV century. For a long time it was considered that the first extant piece of Georgian Literature was "The Martyrdom of the Holy Queen Shushanik" purported to have been written in the V century by Iakob Khutsesi. Though, even then the scientists knew that this written text did not indicate the beginning of the Georgian Literature, but its development in a certain period.

While talking about Georgian Literature we should take into consideration the richest inheritance coming from the pagan period. Except the patterns of materialistic culture it includes the remains of ancient writings preserved in the later literary works, the patterns of folklore and mythos, traditions and the information about the existence of philosophical school in Kolkheti. It should be noted that the adoption of Christianity played a vital role in the formation of Georgian national culture as it is the Christian culture in its essence.

Georgian alphabet is very old. Some of the epigraphic writings are dated back to the 5th century A.D. (Palestine, Bolnisi)

The Georgian original writing is one among the 14 alphabetic writing systems.

The most important event in the history of Georgia was the proclamation of Christianity as the state religion in about 326. Apostle Andrew the First Called was the first to preach Christianity in Georgia. St. Nino has enlightened Georgia and thanks to her Georgia became a Christian country and many churches have been built.

Two ancient genres of Georgian literature are Hagiography and Hymnography.

Georgian Hagiographic writings are documentary by nature and often have poly-genric structure. On the background of the hero’s life one can see the cultural peculiarities of that epoch that make the text more interesting. For this reason in hagiographic works the reflections of all types of ecclesiastic writings are visible: Bibliology, Dogmatics, Polemics, Asceticism, Canonics, Lithurgics, Mysticism, or other Apocryphal writings and studies about Christian Saints and Holy things. It is a part of liturgy and stands close to people, and expresses the national ideals.

Hymnography gave birth to Georgian verse. A vast number of them are the samples for the poets of all times. The unique masterpiece of X century is Mikhael Modrekeli’s “Satselitsdo Iadgari“ introducing a number of Georgian poet Hymnographs (Mikhael Modrekeli, Ioane Minchkhi, Ioane Mtbevari, Kurdanaia, Ezra, Stephane Sananoisidze, Ioane Kinkozisdze). In the following XI-XIII centuries a number of outstanding hymnographs have been added to this list (Ekvtime and Giorgi Atonelebi, King David the Builder and his son Demetre I, philosophers – Ioane Petritsi, Ioane Shavteli, Nikoloz Gulaberisdze and others).

From XI-XII centuries, with the formation of Georgian Kingdom, the Secular writing began to develop.

National culture and literature among them has its heyday of fame. For Georgian Literature this was the epoch of Rustaveli (XII-XIII centuries). Rustaveli's "The Knight in the Panther's skin" together with "Iliad", "Shahnameh" and "The Divine Comedy" is the most important crossroad in the history of the Esthetical development of mankind.

"The Knight in the Panther's skin" reflected the clashing of two huge universes in Georgian culture-The West and the East. The West implies the Christian culture and the East-Persian Poetry. Still this poem is the sample of Christian culture, reflecting the Georgian reality, the period of Renaissance and its culture.

After Rustaveli's Epoch Georgian culture began to fall down. It was caused by the Mongolian invaders and their 3 century reign in Georgia. The revival of literature was noted by the emergence of Persian themes in literature (King Teimuraz and his school).

The outstanding figure of the XVIII century Georgia was Sulkhan Saba Orbeliani. He played an important role in the development of Georgian Prose. His main work was the collection of fables "Sibrdzne Sitsruisa". In addition, he has written "The Voyage in Europe", Georgian Dictionary "Sitkvis Kona", collection of fables "Kilila and Damana"(edited).

Georgian Poet Davit Guramishvili continued the literary principles of Sulkhan Saba Orbeliani. He has collected all his poetry in one book called "Davitiani". It is the Biographical work in its character. It is divided in several parts: Historical part ("Kartli's Chiri"), Didactical part (Stavla Mostavleta"), Pastoral part but the main is the religious part. All these sections are united to form one whole.

From XIX century new Epoch began in the history of Georgian Literature. Georgian Poetry has undergone three main periods of evolution: Classicism, Romanticism and Realism. The formation and flourishing of Georgian Romanticism owes much to Grigol Orbeliani's early poetry and reached its pick in Nikoloz Baratashvili's verses.

The period of realism started in the second half of XIX century. Distinguished representatives of the Georgian realism were Ilia Chavchavadze and Akaki Tsereteli. Later Ilia was canonized as "Saint Ilia the Righteous" by the Georgian Orthodox Church.

Vaja Pshavela's Poetry was an entirely new step in the development of Georgian Realism.

Galaktion Tabidze is regarded as the reformator of the Georgian verse at the beginning of XX century. Galaktion Tabidze and Georgian symbolists (Titsian Tabidze, Paolo Iashvili, Valerian Gaprindashvili, Kolau Nadiradze, Giorgi Leonidze and other Georgian Poets- Grigol Robakidze, Ioseb Grishashvili, Aleksandre Abasheli) played a major role in the development of Georgian Poetry. Innovative directions emerged in Georgian Prose as well. Modernism together with national literary traditions defined these innovations.

The Future tendencies of XX century prose were revealed in the works of Niko Lortkipanidze, Mikheil Javakhishvili, Konstantine Gamsaxurdia, Leo Kiacheli and many others.

In the 30s of XX century Modernism and Avangardism were replaced by Socialistic Realism.

In 60-70s the peculiarities of Socialistic Realism began to disappear in the works of Chabua Amirejibi, Otar Chkheidze, Guram Dochanashvili, Revaz Inanishvili, Rezo Cheishvili, Guram Gegeshidze, Ana Kalandadze, Murman Lebanizde, Mukhran Machavariani and others.

Georgian Literature of Post-Soviet period was a post-modernistic literature (Akaki Morchiladze, Zurab Karumidze, Rati Amaglobeli and etc.).

In general, Georgian Literature is an original writing occupying its special place among other literary works in the world. With the help of Georgian literary works foreign readers are led in an entirely new world.

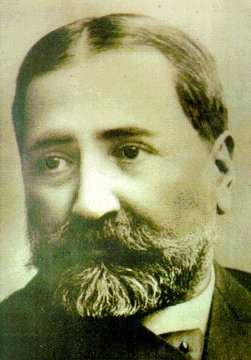

Eduard Ambrosiyevich Shevardnadze (25 January 1928 – 7 July 2014) was a Georgian politician and diplomat. He served as First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party (GPC), the de facto leader of Soviet Georgia from 1972 to 1985 and as Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Soviet Union from 1985 to 1991. Shevardnadze was responsible for many key decisions in Soviet foreign policy during the Gorbachev Era including reunification of Germany. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, he was President of Georgia (or in equivalent posts) from 1992 to 2003. He was forced to retire in 2003 as a consequence of the bloodless Rose Revolution.

Shevardnadze started his political career in the late 1940s as a leading member of his local Komsomol organisation. He was later appointed its Second Secretary, then its First Secretary. His rise in the Georgian Soviet hierarchy continued until 1961 when he was demoted after he insulted a senior official. After spending two years in obscurity, Shevardnadze returned as a First Secretary of a Tbilisi city district, and was able to charge the Tbilisi First Secretary at the time with corruption. His anti-corruption work quickly garnered the interest of the Soviet government and Shevardnadze was appointed as First Deputy of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Georgian SSR. He would later become the head of the internal affairs ministry and was able to charge First Secretary (leader of Soviet Georgia) Vasil Mzhavanadze with corruption.

As First Secretary, Shevardnadze started several economic reforms, which would spur economic growth in the republic—an uncommon occurrence in the Soviet Union because the country was experiencing a nationwide economic stagnation. Shevardnadze's anti-corruption campaign continued until he resigned from his office as First Secretary. Mikhail Gorbachev appointed Shevardnadze to the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs. From then on, with the exception of a brief period between 1990 and 1991, only Gorbachev would outrank Shevardnadze in importance in Soviet foreign policy.

In the aftermath of the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991, Shevardnadze returned to the newly independent Georgia. He became the country's head of state following the removal of the country's first president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia. Shevardnadze was formally elected president in 1995. His presidency was marked by rampant corruption and accusations of nepotism. After allegations of electoral fraud during the 2003 legislative election that led to a series of public protests and demonstrations colloquially known as the Rose Revolution, Shevardnadze was forced to resign. He later lived in relative obscurity and published his memoirs.

| Zviad Gamsakhurdia | served as the president of Georgia from May 26, 1991 until December 31, 1993 | |

| Eduard Shevardnadze | served as the president of Georgia from 26 November 1995 until 23 November 2003 | |

| Mikheil Saakashvili | served as the president of Georgia from 20 January 2008 until 17 November 2013 | |

| Giorgi Margvelashvili | served as the president of Georgia from 17 November 2013 until 16 December 2018 | |

| Salome Zourabichvili | the incumbent president of Georgia since 16 December 2018 |

Opposition pressure on the communist government was manifested in popular demonstrations and strikes, which ultimately resulted in an open, multiparty and democratic parliamentary election being held on October 28, 1990. They were won by the "Round Table" coalition headed by the leading dissident Zviad Gamsakhurdia, who became the head of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia. On March 31, 1991 Gamsakhurdia wasted no time in organising a referendum on independence, which was approved by 98.9% of the votes. Formal independence from the Soviet Union was declared on April 9, 1991, although it took some time before it was widely recognised by outside powers such as the United States and European countries. Gamsakhurdia's government strongly opposed any vestiges of Russian dominance, such as the remaining Soviet military bases in the republic, and (after the collapse of the Soviet Union) his government declined to join the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Gamsakhurdia was elected president on May 26, 1991 with 86% of the vote. He was subsequently widely criticised for what was perceived to be an erratic and authoritarian style of government, with nationalists and reformists joining forces in an uneasy anti-Gamsakhurdia coalition. A tense situation was worsened by the large amount of ex-Soviet weaponry available to the quarreling parties and by the growing power of paramilitary groups. The situation came to a head on December 22, 1991, when armed opposition groups launched a violent military coup d'etat, besieging Gamsakhurdia and his supporters in government buildings in central Tbilisi. Gamsakhurdia managed to evade his enemies and fled to the breakaway Russian republic of Chechnya in January 1992.

The new government invited Eduard Shevardnadze to become the head of a State Council - in effect, president - in March 1992, putting a moderate face on the somewhat unsavoury regime that had been established following Gamsakhurdia's ouster. In August 1992, a separatist dispute in the Georgian autonomous republic of Abkhazia escalated when government forces and paramilitaries were sent into the area to quell separatist activities. The Abkhaz fought back with help from paramilitaries from Russia's North Caucasus regions and alleged covert support from Russian military stationed in a base in Gudauta, Abkhazia and in September 1993 the government forces suffered a catastrophic defeat which led to them being driven out and the entire Georgian population of the region being expelled. Around 14,000 people died and another 300,000 were forced to flee. Ethnic violence also flared in South Ossetia but was eventually quelled, although at the cost of several hundred casualties and 100,000 refugees fleeing into Russian-controlled North Ossetia. In south-western Georgia, the autonomous republic of Ajaria came under the control of Aslan Abashidze, who managed to rule his republic from 1991 to 2004 as a personal fiefdom in which the Tbilisi government had little influence.

On September 24, 1993, in the wake of the Abkhaz disaster, Zviad Gamsakhurdia returned from exile to organise an uprising against the government. His supporters were able to capitalise on the disarray of the government forces and quickly overran much of western Georgia. This alarmed Russia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, and units of the Russian Army were sent into Georgia to assist the government. Gamsakhurdia's rebellion quickly collapsed and he died on December 31, 1993, apparently after being cornered by his enemies. In a highly controversial agreement, Shevardnadze's government agreed that it would join the CIS as part of the price for military and political support.

The April 9 tragedy refers to the events in Tbilisi, Georgia on April 9, 1989, when an anti-Soviet demonstration was dispersed by the Soviet army, resulting in 20 deaths and hundreds of injuries. April 9 is now remembered as the Day of National Unity, an annual public holiday.

The anti-Soviet nationalist movement became more active in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1988. Several strikes and meetings were organized by anti-Soviet political organizations in Tbilisi. The conflict between the Soviet government and Georgian nationalists deepened after the so-called Lykhny Assembly on March 18, 1989, when several thousand Abkhaz demanded secession from Georgia and restoration of the Union republic status of 1921–1931. In response, the anti-Soviet groups organized a series of unsanctioned meetings across the republic, claiming that the Soviet government was using Abkhaz separatism in order to oppose the nationalist movement. The protests reached their peak on April 4, 1989, when tens of thousands of Georgians gathered before the House of Government on Rustaveli Avenue in Tbilisi. The protesters, led by the Independence Committee (Merab Kostava, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, Giorgi Chanturia, Irakli Bathiashvili, Irakli Tsereteli and others) organized a peaceful demonstration and hunger strikes, demanding the punishment of Abkhaz secessionists and restoration of Georgian independence. Local communist authorities lost control over the situation in the capital and were unable to contain the protests.

The demonstrations

In the evening of April 8, 1989, Colonel General Igor Rodionov, Commander of the Transcaucasus Military District, ordered his troops to mobilize. Moments before the attack by the Soviet forces, the Patriarch of Georgia Ilia II addressed the demonstrators asking them to leave the Rustaveli avenue and the vicinities of the government building due to the danger which accumulated during the day after the appearance of Soviet tanks near the avenue. The demonstrators refused to disband even after the Patriarchs plea. The local Georgian militsiya (police) units were disarmed just before the operation. On April 9, at 3:45 a.m., Soviet tanks and troops under General Aleksandr Lebed surrounded the demonstration area. The Soviet troops received an order from General Rodionov to disband and clear the avenue from demonstrators by any means necessary. [1]

The Soviet detachment, armed with military batons and metal shovels, advanced on demonstrators by encircling them from all sides leaving only the narrow pathway to pull back. As the results of the advance, the soldiers started to attack demonstrators by using small metal military shovels, inflicting blows to anyone who was struck. [2] One of the victims of such attack was the 16 year old girl who tried to get away from the advancing soldiers but was chased by the soldiers near the steps of the government building and killed by shovel blows to the head and chest. She was dragged out by her mother who was also attacked and wounded. This particular violent attack was recorded by the video from the balcony of the building located on the other side of the avenue, which was used during the Sobchaks investigation of the events in the aftermath. Similar attacks by Soviet soldiers on nineteen women who were later killed was conformed by the investigation report. [3] It was also reported that toxic gas was used against the demonstrators resulting in vomiting, respiratory problems and sudden paralyses of the nervous system were reported. [4]

Twenty people, mainly young girls and older women, were killed and over 4,000 were injured due to toxic gas and injuries received from violent beating by batons and shovels. [5]. The disarmed police officers attempted evacuate panicked people, however a video taken secretly by opposition journalists showed that soldiers did not allow emergency doctors to help injured people, in fact even ambulance cars were attacked by the advancing soldiers[6] Captured on film, the image of a young man beating a tank with a stick became a symbol of the Georgian anti-Soviet movement. [7]

On April 10, the Soviet government issued the statement blaming the demonstrators for causing unrest and danger for the safety of the public. Next day, the Georgian TV showed the bodies of the 19 women violently killed, demonstrating that the extreme brutality was used by the Soviet soldiers as the faces of the deceased women were hard to identify due to the facial injured and blows to the head. The Soviet government blamed the demonstrators for the death of 20 people, claiming that the demonstrators trampled each other while panicking and retreating from the advancing soviet soldiers. [8] However, Parliamentary commission on investigation of events of April 9, 1989 in Tbilisi was launched by Anatoly Sobchak, member of Congress of People's Deputies of Soviet Union. After full investigation and inqueries, the commission concluded the following: The commission condemned the military, which had caused so many deaths trying to disperse demonstrators. The commission's report made it more difficult to use military power against demonstrations of civil unrest in the Soviet Union and Russia. Sobchak's report presented the detailed account of the violence which was used against the peaceful demonstrators and recommended the full persecution of military personnel held responsible for the April 9 event. [9]

Aftermath

On April 10, in protest against the crackdown, Tbilisi and the rest of Georgia went out on strike and a 40-day period of mourning was declared. People brought massive collections of flowers to the place of the killings. A state of emergency was declared, but demonstrations continued.

The government of Soviet Georgia resigned as a result of the event. Moscow claimed the demonstrators attacked first and the soldiers had to repel them. At the first Congress of the USSR People's Deputies (May–June 1989) Mikhail Gorbachev disclaimed all responsibility, shifting blame onto the army. The revelations in the liberal Soviet media, as well as the findings of the "pro-Perestroika" Deputy Anatoly Sobchak's commission of enquiry into the Tbilisi events, reported at the second Congress in December 1989, resulted in embarrassment for the Soviet hardliners and army leadership implicated in the event.

Legacy

The April 9 tragedy radicalised Georgian opposition to Soviet power. A few months later, a session of the Supreme Council of Georgian SSR, held on November 17-November 18, 1989, officially condemned the occupation and annexation of Democratic Republic of Georgia by Soviet Russia in 1921.

On April 9, 1991, on the second anniversary of the tragedy, the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia proclaimed Georgian sovereignty and independence from the Soviet Union according to the March 31, 1991 referendum results.

A memorial to the victims of the tragedy was opened at the location of the crackdown on Rustaveli Avenue on November 23, 2004.

References

1. New Nations Rising: The Fall of the Soviets and the Challenge of Independence, Nadia Diuk, Adrian Karatnycky

2. New Nations Rising: The Fall of the Soviets and the Challenge of Independence, Nadia Diuk, Adrian Karatnycky

3. New Nations Rising: The Fall of the Soviets and the Challenge of Independence, Nadia Diuk, Adrian Karatnycky

4. Nationalist Violence and the State: Political Authority and Contentious Repertoires in the Former USSR, Mark R. Beissinger Comparative Politics, Vol. 30, No. 4 (Jul., 1998), pp. 26-27.

5. Georgia: A Sovereign Country in the Caucasus Roger Rosen, p. 89

6. Defending the Border: Identity, Religion, And Modernity in the Republic of Georgia (Culture and Society After Socialism) , Mathijs Pelkmans pp. 127-39

7. Georgia: In the Mountains of Poetry, Peter Nasmyth, p 18

8. Georgia: In the Mountains of Poetry, Peter Nasmyth, p 18

9. Nationalist Violence and the State: Political Authority and Contentious Repertoires in the Former USSR, Mark R. Beissinger Comparative Politics, Vol. 30, No. 4 (Jul., 1998), pp. 26-27.