Opposition pressure on the communist government was manifested in popular demonstrations and strikes, which ultimately resulted in an open, multiparty and democratic parliamentary election being held on October 28, 1990. They were won by the "Round Table" coalition headed by the leading dissident Zviad Gamsakhurdia, who became the head of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia. On March 31, 1991 Gamsakhurdia wasted no time in organising a referendum on independence, which was approved by 98.9% of the votes. Formal independence from the Soviet Union was declared on April 9, 1991, although it took some time before it was widely recognised by outside powers such as the United States and European countries. Gamsakhurdia's government strongly opposed any vestiges of Russian dominance, such as the remaining Soviet military bases in the republic, and (after the collapse of the Soviet Union) his government declined to join the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Gamsakhurdia was elected president on May 26, 1991 with 86% of the vote. He was subsequently widely criticised for what was perceived to be an erratic and authoritarian style of government, with nationalists and reformists joining forces in an uneasy anti-Gamsakhurdia coalition. A tense situation was worsened by the large amount of ex-Soviet weaponry available to the quarreling parties and by the growing power of paramilitary groups. The situation came to a head on December 22, 1991, when armed opposition groups launched a violent military coup d'etat, besieging Gamsakhurdia and his supporters in government buildings in central Tbilisi. Gamsakhurdia managed to evade his enemies and fled to the breakaway Russian republic of Chechnya in January 1992.

The new government invited Eduard Shevardnadze to become the head of a State Council - in effect, president - in March 1992, putting a moderate face on the somewhat unsavoury regime that had been established following Gamsakhurdia's ouster. In August 1992, a separatist dispute in the Georgian autonomous republic of Abkhazia escalated when government forces and paramilitaries were sent into the area to quell separatist activities. The Abkhaz fought back with help from paramilitaries from Russia's North Caucasus regions and alleged covert support from Russian military stationed in a base in Gudauta, Abkhazia and in September 1993 the government forces suffered a catastrophic defeat which led to them being driven out and the entire Georgian population of the region being expelled. Around 14,000 people died and another 300,000 were forced to flee. Ethnic violence also flared in South Ossetia but was eventually quelled, although at the cost of several hundred casualties and 100,000 refugees fleeing into Russian-controlled North Ossetia. In south-western Georgia, the autonomous republic of Ajaria came under the control of Aslan Abashidze, who managed to rule his republic from 1991 to 2004 as a personal fiefdom in which the Tbilisi government had little influence.

On September 24, 1993, in the wake of the Abkhaz disaster, Zviad Gamsakhurdia returned from exile to organise an uprising against the government. His supporters were able to capitalise on the disarray of the government forces and quickly overran much of western Georgia. This alarmed Russia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, and units of the Russian Army were sent into Georgia to assist the government. Gamsakhurdia's rebellion quickly collapsed and he died on December 31, 1993, apparently after being cornered by his enemies. In a highly controversial agreement, Shevardnadze's government agreed that it would join the CIS as part of the price for military and political support.

The April 9 tragedy refers to the events in Tbilisi, Georgia on April 9, 1989, when an anti-Soviet demonstration was dispersed by the Soviet army, resulting in 20 deaths and hundreds of injuries. April 9 is now remembered as the Day of National Unity, an annual public holiday.

The anti-Soviet nationalist movement became more active in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1988. Several strikes and meetings were organized by anti-Soviet political organizations in Tbilisi. The conflict between the Soviet government and Georgian nationalists deepened after the so-called Lykhny Assembly on March 18, 1989, when several thousand Abkhaz demanded secession from Georgia and restoration of the Union republic status of 1921–1931. In response, the anti-Soviet groups organized a series of unsanctioned meetings across the republic, claiming that the Soviet government was using Abkhaz separatism in order to oppose the nationalist movement. The protests reached their peak on April 4, 1989, when tens of thousands of Georgians gathered before the House of Government on Rustaveli Avenue in Tbilisi. The protesters, led by the Independence Committee (Merab Kostava, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, Giorgi Chanturia, Irakli Bathiashvili, Irakli Tsereteli and others) organized a peaceful demonstration and hunger strikes, demanding the punishment of Abkhaz secessionists and restoration of Georgian independence. Local communist authorities lost control over the situation in the capital and were unable to contain the protests.

The demonstrations

In the evening of April 8, 1989, Colonel General Igor Rodionov, Commander of the Transcaucasus Military District, ordered his troops to mobilize. Moments before the attack by the Soviet forces, the Patriarch of Georgia Ilia II addressed the demonstrators asking them to leave the Rustaveli avenue and the vicinities of the government building due to the danger which accumulated during the day after the appearance of Soviet tanks near the avenue. The demonstrators refused to disband even after the Patriarchs plea. The local Georgian militsiya (police) units were disarmed just before the operation. On April 9, at 3:45 a.m., Soviet tanks and troops under General Aleksandr Lebed surrounded the demonstration area. The Soviet troops received an order from General Rodionov to disband and clear the avenue from demonstrators by any means necessary. [1]

The Soviet detachment, armed with military batons and metal shovels, advanced on demonstrators by encircling them from all sides leaving only the narrow pathway to pull back. As the results of the advance, the soldiers started to attack demonstrators by using small metal military shovels, inflicting blows to anyone who was struck. [2] One of the victims of such attack was the 16 year old girl who tried to get away from the advancing soldiers but was chased by the soldiers near the steps of the government building and killed by shovel blows to the head and chest. She was dragged out by her mother who was also attacked and wounded. This particular violent attack was recorded by the video from the balcony of the building located on the other side of the avenue, which was used during the Sobchaks investigation of the events in the aftermath. Similar attacks by Soviet soldiers on nineteen women who were later killed was conformed by the investigation report. [3] It was also reported that toxic gas was used against the demonstrators resulting in vomiting, respiratory problems and sudden paralyses of the nervous system were reported. [4]

Twenty people, mainly young girls and older women, were killed and over 4,000 were injured due to toxic gas and injuries received from violent beating by batons and shovels. [5]. The disarmed police officers attempted evacuate panicked people, however a video taken secretly by opposition journalists showed that soldiers did not allow emergency doctors to help injured people, in fact even ambulance cars were attacked by the advancing soldiers[6] Captured on film, the image of a young man beating a tank with a stick became a symbol of the Georgian anti-Soviet movement. [7]

On April 10, the Soviet government issued the statement blaming the demonstrators for causing unrest and danger for the safety of the public. Next day, the Georgian TV showed the bodies of the 19 women violently killed, demonstrating that the extreme brutality was used by the Soviet soldiers as the faces of the deceased women were hard to identify due to the facial injured and blows to the head. The Soviet government blamed the demonstrators for the death of 20 people, claiming that the demonstrators trampled each other while panicking and retreating from the advancing soviet soldiers. [8] However, Parliamentary commission on investigation of events of April 9, 1989 in Tbilisi was launched by Anatoly Sobchak, member of Congress of People's Deputies of Soviet Union. After full investigation and inqueries, the commission concluded the following: The commission condemned the military, which had caused so many deaths trying to disperse demonstrators. The commission's report made it more difficult to use military power against demonstrations of civil unrest in the Soviet Union and Russia. Sobchak's report presented the detailed account of the violence which was used against the peaceful demonstrators and recommended the full persecution of military personnel held responsible for the April 9 event. [9]

Aftermath

On April 10, in protest against the crackdown, Tbilisi and the rest of Georgia went out on strike and a 40-day period of mourning was declared. People brought massive collections of flowers to the place of the killings. A state of emergency was declared, but demonstrations continued.

The government of Soviet Georgia resigned as a result of the event. Moscow claimed the demonstrators attacked first and the soldiers had to repel them. At the first Congress of the USSR People's Deputies (May–June 1989) Mikhail Gorbachev disclaimed all responsibility, shifting blame onto the army. The revelations in the liberal Soviet media, as well as the findings of the "pro-Perestroika" Deputy Anatoly Sobchak's commission of enquiry into the Tbilisi events, reported at the second Congress in December 1989, resulted in embarrassment for the Soviet hardliners and army leadership implicated in the event.

Legacy

The April 9 tragedy radicalised Georgian opposition to Soviet power. A few months later, a session of the Supreme Council of Georgian SSR, held on November 17-November 18, 1989, officially condemned the occupation and annexation of Democratic Republic of Georgia by Soviet Russia in 1921.

On April 9, 1991, on the second anniversary of the tragedy, the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia proclaimed Georgian sovereignty and independence from the Soviet Union according to the March 31, 1991 referendum results.

A memorial to the victims of the tragedy was opened at the location of the crackdown on Rustaveli Avenue on November 23, 2004.

References

1. New Nations Rising: The Fall of the Soviets and the Challenge of Independence, Nadia Diuk, Adrian Karatnycky

2. New Nations Rising: The Fall of the Soviets and the Challenge of Independence, Nadia Diuk, Adrian Karatnycky

3. New Nations Rising: The Fall of the Soviets and the Challenge of Independence, Nadia Diuk, Adrian Karatnycky

4. Nationalist Violence and the State: Political Authority and Contentious Repertoires in the Former USSR, Mark R. Beissinger Comparative Politics, Vol. 30, No. 4 (Jul., 1998), pp. 26-27.

5. Georgia: A Sovereign Country in the Caucasus Roger Rosen, p. 89

6. Defending the Border: Identity, Religion, And Modernity in the Republic of Georgia (Culture and Society After Socialism) , Mathijs Pelkmans pp. 127-39

7. Georgia: In the Mountains of Poetry, Peter Nasmyth, p 18

8. Georgia: In the Mountains of Poetry, Peter Nasmyth, p 18

9. Nationalist Violence and the State: Political Authority and Contentious Repertoires in the Former USSR, Mark R. Beissinger Comparative Politics, Vol. 30, No. 4 (Jul., 1998), pp. 26-27.

During the Georgian Affair of 1922, Georgia was forcibly incorporated into the Transcaucasian SFSR comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. The Soviet Government forced Georgia to cede several areas to Turkey (the province of Tao-Klarjeti and part of Batumi province), Azerbaijan (the province of Hereti/Saingilo), Armenia (the Lore region) and Russia (part of the Black Sea seacost and a northeastern corner of Khevi, eastern Georgia). Soviet rule was harsh: about 50,000 people were executed and killed in 1921-1924, more than 150,000 were purged under Stalin and his secret police chief, the Georgian Lavrenty Beria in 1935-1938, 1942 and 1945-1951. In 1936, the TFSSR was dissolved and Georgia became the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Reaching the Caucasus oilfields was one of the main objectives of Hitler's invasion of the USSR in August 1941, but the armies of the Axis powers did not get as far as Georgia. The country contributed almost 700,000 fighters (350,000 were killed) to the Red Army, and was a vital source of textiles and munitions. However, a number of Georgians fought on the side of the German armed forces, forming the Georgian Legion.

Stalin's successful appeal for patriotic unity eclipsed Georgian nationalism during the war and diffused it in the years following. Khrushchev's policy of de-Stalinization was followed by a general criticism of the whole Georgian people and culture. On March 9, 1956, hundreds of Georgian students were killed when they demonstrated against Khrushchev.

The decentralisation program introduced by Khrushchev in the mid-1950s was soon exploited by Georgian Communist Party officials to build their own regional power base. A thriving capitalist shadow economy emerged alongside the official state-owned economy, making Georgia one of the most economically successful Soviet republics but unfortunately also greatly increasing corruption.

Although corruption was hardly unknown in the Soviet Union, it became so widespread and blatant in Georgia that it came to be an embarrassment to the authorities in Moscow. The country's interior minister between 1964 and 1972, Eduard Shevardnadze, gained a reputation as a fighter of corruption and engineered the removal of Vasil Mzhavanadze, the corrupt First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party. Shevardnadze ascended to the post of First Secretary with the blessings of Moscow. He was an effective and able ruler of Georgia from 1972 to 1985, improving the official economy and dismissing hundreds of corrupt officials. Soviet power and Georgian nationalism clashed in 1978 when Moscow ordered revision of the constitutional status of the Georgian language as Georgia's official state language. Bowing to pressure from mass street demonstrations on April 14, 1978 Moscow approved Shevardnadze's reinstatement of the constitutional guarantee the same year. April 14 was established as a Day of the Georgian Language.

Shevardnadze's appointment as Soviet Foreign Minister in 1985 caused him to be replaced as Georgian leader by Jumber Patiashvili, a conservative and generally ineffective Communist who coped poorly with the challenges of Perestroika. Towards the end of the late 1980s there were increasingly violent clashes between the Communist authorities, the resurgent Georgian nationalist movement and nationalist movements in Georgia's minority-populated regions (notably South Ossetia). On 9 April 1989, Soviet troops were used to break up a peaceful demonstration at the government building in Tbilisi. Twenty Georgians were killed and hundreds wounded and poisoned. The event radicalised Georgian politics, prompting many - even some Georgian communists - to conclude that independence was preferable to continued Soviet rule.

|

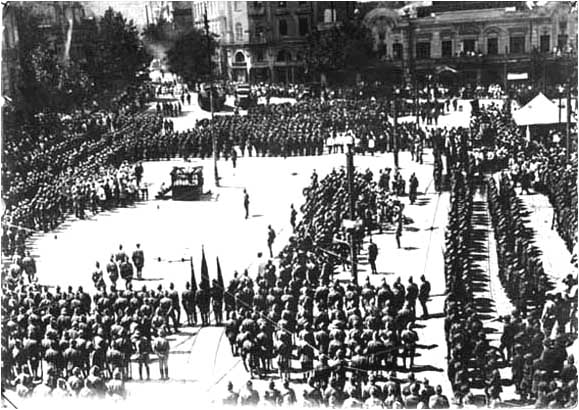

Declaration of independence by the Georgian parliament, 1918 |

The Russian Revolution of October 1917 plunged Russia into a bloody civil war during which several outlying Russian territories declared independence. Georgia was one of them, proclaiming the establishment of the independent Democratic Republic of Georgia (DRG) on May 26, 1918. The new country was ruled by the Menshevik faction of the Social Democratic Party, which established a multi-party system in sharp contrast with the "dictatorship of the proletariat" established by the Bolsheviks in Russia. It was recognised by Soviet Russia (Treaty of Moscow (1920)) and the major Western powers in 1921.

|

|

In February, 1921 the Red Army invaded Georgia and after a short war occupied the country. The Georgian government was forced to flee. Guerilla resistance in 1921-1924 was followed by a large-scale patriotic uprising in August, 1924. Colonel Kakutsa Cholokashvili was one of the most prominent guerilla leaders in this phase.

|

The 11th Red Army of the Russian SFSR occupies Tbilisi, 25 February 1921 |

Son of King David VII and his wife Gvantsa, Demetrius was only 2 years old when his mother was killed by the Mongols in 1261. He succeeded on his father's death in 1270, when he was 11 years old. He ruled under the regency of Sadun Mankaberdeli for some time. In 1277–1281, he took part in Abaqa Khan's campaigns against Egypt and in particularly distinguished himself at the Second Battle of Homs, (29 October 1281). Although he continued to be titled "king of Georgians and Abkhazians, etc", Demetrius’s rule extended only over the eastern part of the kingdom. Western Georgia was under the rule of the Imeretian branch of the Bagrationi dynasty.

King Demetrius was considered quite a controversial person. Devoted to Christianity, he was criticized for his polygamy.[citation needed] In 1288, on the order of Arghun Khan, he subdued the rebel province of Derbend at the Caspian Sea. The same year, Arghun revealed a plot organized by his powerful minister Buqa, whose son was married to Demetrius's daughter. Bugha and his family were massacred, and the Georgian king, suspected to be involved in a plot, was ordered to the Mongol capital, or Arghun threatened to invade Georgia. Despite much advice from nobles, Demetrius headed for the Khan’s residence to face apparent death, and was imprisoned there. He was beheaded at Movakan on 12 March 1289. He was buried at Mtskheta, Georgia, and canonized by the Georgian Orthodox Church.

He was succeeded by his cousin Vakhtang II.

|

After the long period of Russian annexation and eventual abolition of Georgian monarchy and autocephalous status of the Georgian church by the Russian empire, Georgia plunged into cultural and national disintegration. Georgian churches and monasteries were governed by the Russian clergy who outlawed the Georgian liturgy and desecrated medieval Georgian frescos on various churches all across Georgia. Between the years of 1855 to 1907, the Georgian patriotic movement was launched under the leadership of Prince Ilia Chavchavadze, world renowned poet, novelist and orator. Chavchavadze financed new Georgian schools and supported the Georgian national theatre. In 1877 he launched the newspaper Iveria which played an important part in reviving Georgian national consciousness. His strive for national awakening was welcomed by the leading Georgian intellectuals of that time, Giorgi Tsereteli, Ivane Machabeli, Akaki Tsereteli, Niko Nikoladze, Alexander Kazbegi, Iakob Gogebashvili, etc.

Monument of Ilia Chavchavadze und Akaki Tsereteli in Tbilisi

|