His poems are viewed as classical works of Georgian literature. His poetry was mostly patriotic based on Georgian cultural and religious values, but normally loyal to Soviet ideology. He welcomed Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika and supported the Soviet-era dissident Zviad Gamsakhurdia when he came to power and led Georgia to the declaration of independence in 1991. Abashidze died in Tbilisi in 1992 and was afforded a state funeral. He was 82.

A Word on Shot'ha Rust'hveli

Translated from the Georgian by Lyn Coffin and Nato Alhazishvili

Monastery in the Hills

(Monk's Song)

Each morning I fetch water from a hidden spring

and quietly watch the changing clouds.

I do not know if I will see another winter

but I am still happy, surrounded by mountains and green places

where so many mortals—so many weak ones—live.

I do not think about the pines because they're me.

Each time they think of me,

I stop wondering why the white walls of my retreat

do not look like snow on the bamboo fence.

The paths of fishermen and woodcutters intertwine

and even after a hundred years I would not want to untangle them

Nor am I tired by memories of a past I never had

Nor do I believe my prayers are heard by

a blue deer, kneeling, whose quiet breathing I can almost touch fully, with my body.

I wonder where Sesson is now.

These plum branches await only night and the moon

to startle my long ago dreams

and scatter them on these roofs and this place

numerously inhabited by clouds and forests and squirrels

and these wild geese

and the spring hidden to everyone

and that which wanders on mountain paths

and cold cruel winds and dry brush

gathered near the monastery

on which to cook beans for forty years.

Every twilight, cranes follow the wind toward my thoughts

but they do not think of me at all;

I cannot find the way home because

I have never wished to find it.

I lie on the ground like a branch

My bones are as dry as brushwood.

If they asked me, I could not tell them the name

of the woman who was with me once,

who was with me once and warmed my heart.

The rain is sleeping.

Every branch, every treetop, is a warm human soul and

(now I realize) every breath of the wind

every snow-covered leaf on the slope of a hill is like this.

I fetch water from the hidden spring.

Cranes in Flight

Each of them: not in the sky or the mirror of an old lake,

but in the field of nearly imperceptible resistance

created by the wave of

one wing to the left or one wing to the right—

A wave of birds

Each of them: not advancing with respect to another

but—in an unending current

towards fate,

fate not reduced to

any of the possible triangles or heavens

neither to the sight-defying touch of the

crossable or the transformed into sorrow

Each of them

exists, not in a separate being or in separate seconds,

but in a moving mystery,

bestowable

the first touch being the sound

accompanying

discovered

Each of them: not against trees or Earth

or memory

but into the law unknown to them:

marking line and curve

Each

in unending movement

Every second in the fragile

thick lake of the mirror

Still Life with Snow

(To Carmela Uranga)

on airy balconies, heavy houses,

speeding cars, all these snows—

snow burying its head in someone's airy balcony

or living on the roof of an instantaneous car

or running stealthily after silly children—

lost street by street, all these snows

or at night in small parks of gathered friendships

trampled by thousands of feet

all these hearts of all these snows

fall like silent touches

unnoticed reprimands

the whole life of half-melted snow

sunrise to sunset,

the whole half-melted life of snow

an everyday this or that person

wakes up to a this or that surprise

that this snow is completely other

and under the cover of some other unknown snow

an everyday other unknown person

sees another dream, and in the dream

more than one other snow:

in a corner of the house, unnoticed, it is bitterly burying its head

or step by step ascending a mountain's far off slopes

or paling after chasing silly children

or, as it often happens,

failing to fall.

genius loci

For Hans Magnus Enzensberger

in a dreary café in Copenhagen, capital of Austria

with a few not so bad views over river Seine

I watch its interior full of tired and heat-worn people

the waiter briskly brings my pizza

and says with a stern smile:

"please, enjoy

it is almost like the ones mothers make

in the towns of my native Italy:

Vienna or Madrid or Bern"

the pizza tastes good indeed I haven't eaten all day

just some dried figs from a distant supermarket

at the Saint Mark's Square

an elderly man in a green top hat sits across from me

and stares into the newspaper with indignation:

"why did they disperse this demonstration in London

they weren't asking for much just the ban on unsafe products

such insolence is unheard of from Belgian police

but no wonder the police always win"

I nod in agreement

and glance involuntarily

at his shabby mouse-gray jacket

"I bought this ten years ago in New Delhi, capital of Kazakhstan

nothing else remains with me from there except sweet memories

which this jacket always carries with me

but here in Sierra Leone people are strange

I wonder if every Hungarian is like this including you"

"I am not from here

I am a traveler from a hot land

you may have heard of Georgia"

"of course, of course

once as a tourist I visited

your beautiful capital Sofia

I haven't been there in ages though

it must have changed by now"

"what can I say it looks like Beijing to a foreign eye"

"you mean the capital of Sweden?"

the man stands up sets the folded newspaper on the table like a heavy iron pot

nods good-bye and leaves the café with a wobble

I watch his stooped back

and for a second feel how he smiles

for I also think like him

that I will never again see him in this city

which is probably not as populous as

for example Ankara, capital of Japan

or Tartu, capital of Nigeria

then I return to my pizza but keep wondering

how much the marks of my memories will weigh in twenty years

and will my jacket or a t-shirt or some person

in some dreary café in some city share this mounting weight

or will I be able to cut anything out of it

such as every meal I've savored in Salzburg, Poland

or the memory of Spanish wine from Tirana, capital of Bulgaria

or aimless journeys in countryside haulage in

Munich, the provincial town in Czech lands

forget it—my thought tells me—this is all madness

continue living the life which is as beautiful as

for example the Moldova

so fleetingly lapping

in the eternal Portuguese town of Zurich

like a spy tiptoeing

towards the everyday nerves of its citizens

or for example the Donau

protecting like a wise serpent Stockholm, capital of Peru,

where at the last century's end

couples often walked the streets with songs like this

"this river like so many others

cannot often see the sun for the clouds

but the clouds can never ever

hide the sun from our eyes"

continue with the life you don't know? To whom do I say

do not give me so many memories hidden away in so many lives

do not give me so many solitudes I can never return

do not give me forgotten dervishes and forgotten madmen

forgotten books forgotten love-stories

do not give me these passages from reference-books and encyclopedias:

"belongs to the ranks of forgotten authors"

do not make me read what is not written by poets

of course I know well that my guardian spirits

join battles of life and death

even here in the dreary café of Belgrade, capital of Finland,

so as not to overcome each other, so my love will not burn out

but still do not make me read what is not written by poets

my Turkish pizza is almost finished

but in my memory it is just as pure

as when I first saw it

when they brought its heart to me

as a torch for all tomorrows

Killer's Song

(traditional-romantic)

1.

I killed him.

I killed him very well.

I killed him very elegantly and precisely.

2.

I prepared for this minute for such a long time!

All my life I prepared for this minute.

My whole life prepared me for this minute.

The whole universe prepared me for this minute.

And it—the universe—knew that this would happen.

And it—the universe—took my side as always

And if I had not committed this act, there would be no second coming.

And if it came, it would not matter.

That's why I had to open the knife unerringly.

My knife had to do the work and I had to become its servant.

3.

I had a knife in my chest pocket,

A good knife.

And I opened the knife as easily and quickly

As if I were the knife itself.

4.

I was glad, I was very glad

Happiness was also glad, glad like me.

Oh, how glad it was! Oh, how it loved me!

Oh, how sweetly it caressed me with words as true and unerring as a knife!

5.

The one I killed, he wasn't my target;

The one I slashed, he wasn't my target;

This minute was my target. This happy age was my target—

The best time in the universe;

This unexpected order, this unexpected sweltering;

This, the feast—whose coming you can't force

The feast—that always comes on its own!

6.

It would be desirable—to shove it into the heart

To enter the heart directly!

But the heart is teeny-tiny,

And locked in its cage of bones,

Peeping sadly and shivering out of the ribs.

Obviously, a rib can get stubborn and deny admission!

And, for a second, I considered the case:

A rib might screech and take the thrust;

Then blood would be spilled in vain.

Would be spilled to disappoint my knife.

Would be spilled in vain and spell failure for my knife.

It seems it would be more reliable to enter the abdomen,—

Somewhere near the navel: right or left, above or below.

What enters will also turn or slide for a couple of seconds,

Somewhere toward the liver or the navel—Mecca of the abdomen.

But for a knife, clothing is what armor is for a sword;

Especially if the abdomen is dense and hard.

It would therefore be more reliable to split the neck,—

Arteries would untie and I could see the gullet,

Now already severed in two—frolicking on both banks

Oh, how terribly I was afraid the devil wouldn't play his part!

Oh, how terribly I was afraid I wouldn't kill him!

Terrified of not killing!

7.

But I still settled on entering the heart and that's what I did.

And the knife so quietly and so calmly found

Both the heart and its cautious heartbeat that I instantly realized:

They had known each other a long, long time,

They had looked for each other for a long, long time,

And when they saw each other, they were not confused,—

They both together stretched their arms out to God,

They both together pointed their fingers at God,

And these two roads, these two directions

Convened: they never went any farther.

There, undoubtedly, God was standing and did not think

About me, nor about the one I killed;

Nor did he think of the knife, become long ago part of my hand.

And I would be very happy to know

that he thought:

"It's good that there is death and someone

Who can kill the ones deserving death".

And these two roads appreciated and attained each other,

And the knife and its humble servant were victorious.

It entered where it should have entered without any doubt.

And I observed how my knife killed the person,

Who once insulted freedom, insulted another,

Equally defenseless, equally miserable,

Equally produced by our land and our air

Soaked with the smell of so many tormentors' glances,

Fetid with so many hidden glances,

Produced by this land where so many resemble each other,

But not my reliable knife,

Which was as faithful to me as I was to memory.

To memory which is the bridge, which is survival.

8.

I did not smell the smell of blood,

Nor the smell of the person on his deathbed.

I just shoved my knife in and was glad

That I did it reliably- And I observed

That the blood did not go anywhere,

The blood lingered close to the body.

9.

I was glad and thought: if this knife were the only one

That could protect human dignity

That could protect its own dignity and memory—

And protect the one who could not survive because

Then the knife did not exist which could protect her,

Nor the one who understands that now, this minute,

She is protected with his own pain and memory—

Then this knife is my God

And I love this knife

As I love my life standing by the head of the one I killed with the knife in my hand

As I love it every time every place I hold this knife in my hand,

As I love everything that isn't like anyone or anything else

As I love this life that is very lonesome

And is—simply—everything that happens on this terribly cruel earth.

Translated from the Georgian by Lyn Coffin and Nato Alhazishvili

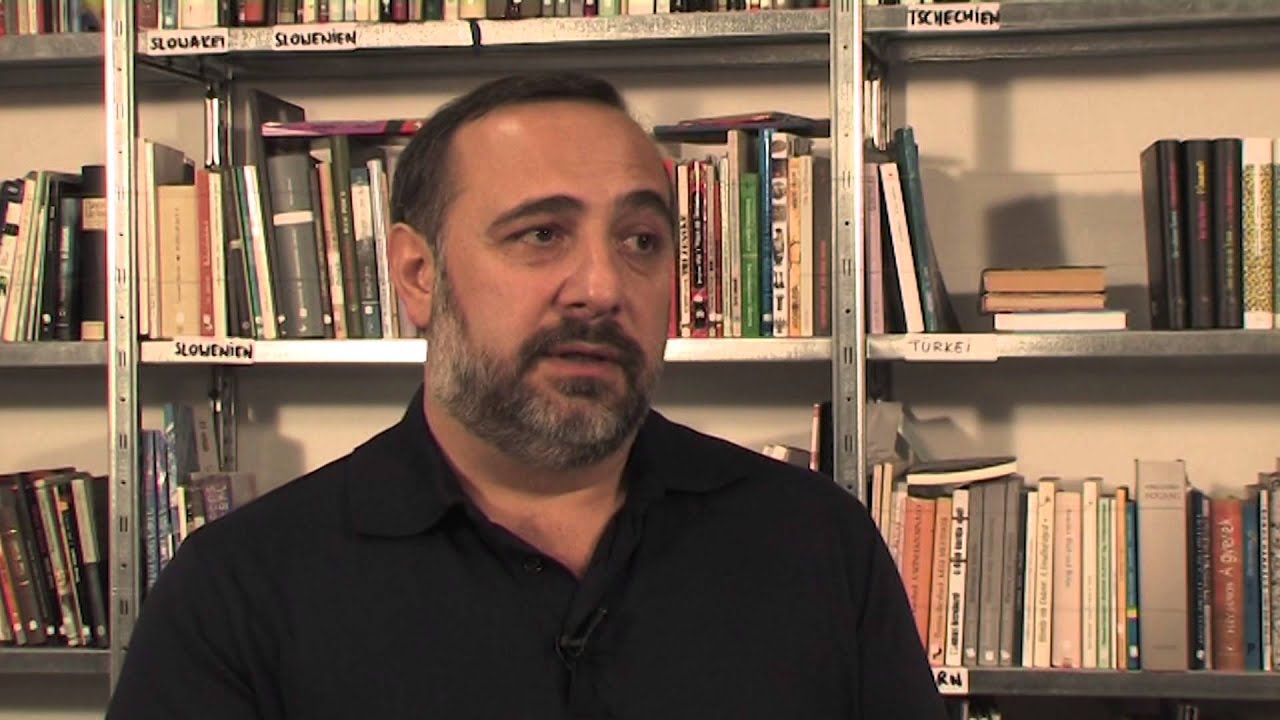

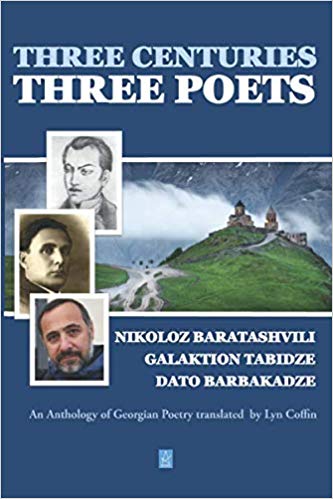

Dato Barbakadze's poetry in some ways might be said to further the exploration of language initiated by Gertrude Stein and extended by some of the "Language" poets of the U.S.A. "In the beginning was language, and all that language should have expressed / In the beginning was a tower, and all who should have destroyed it / In the beginning was hope, and all who should have been skilled in hope..." he writes in "Classical Disharmony," eschewing narrative and lyrical modes in favor of achieving a cumulative and philosophic modality.

These earliest poems were written in the 1980s during an energy crisis in Tbilisi, composed by candle or kerosene light while the poet lived in a state of perpetual hunger. They carry a sense of bitter winters, the poet says, when he was sleeping in his clothes, his apartment frozen. The poet immersed himself in the writings of Pasternak, Celan, Musil, Greek literature, medieval German mystics, Thackeray, Pascal, Blake, American poets, nineteenth century French novelists, Hegel, Fitzgerald, Henry Miller, French structuralists, psychiatric literature. Surprisingly he does not mention Stein here, and Wittgenstein comes only later. The latter's observation, "The limits of my language mean the limits of my world," would fit comfortably within Barbakadze's earlier poems.

Mention "philosophical poetry" in the U.S.A., and one can almost hear the infinite number of eyelids slamming shut. And yet all of our best poetry at least implies a philosophical stance toward reality. The opening lines of "Thieves" might have been written by Brecht while pondering the nature of capitalism:

"They stole what was mine.

From then on I could only give what wasn't mine.

I never knew how what wasn't mine became mine.

And I did not know how to bestow it.

I had no other way but to steal what belonged to another,

in order to understand how to steal what belongs to another.

As soon as I stole what wasn't mine, I realized

that before I could grant what wasn't mine

it would be stolen. And I also realized that I had stolen

what really belonged to whomever I stole it from, though it wasn't his..."

In a long dramatic monologue, he takes on the persona of a killer who finds his knife to be his god, concluding:

9.

...Then this knife is my God

And I love this knife

As I love my life standing by the head of the one I killed with the

knife in my hand

As I love it every time everywhere I hold this knife in my hand,

As I love everything that isn't like anyone or anything else

As I love this life that is very lonesome

And is—simply—everything that happens on this terribly cruel

earth.

Can or should the poem be read with overtly political implications, as well as the more obvious morality tale it unfolds? Where the world is harsh and cruel, the poet struggles to understand from an imaginative point of view. He needn't name names or call out figures of state to make his insights clear.

Later poems were written during a more tranquil stay in a Georgian monastery that dates from the Middle Ages, and still others during a stay in Germany. It was there that he turned to Wittgenstein, Descartes and others, along with classical German literature. Beginning with "Monastery in the Hills," the poems adopt a calmer, less tortured tone, while still revealing a deeply questioning philosophical engagement with his immediate environment, as in these opening lines from "Monastery":

Each morning I fetch water from a hidden spring

and quietly watch the changing clouds.

I do not know if I will see another winter

but I am still happy, surrounded by mountains and green places

where so many mortals—so many weak ones—live.

I do not think about the pines because they're me.

Each time they think of me,

I stop wondering why the white walls of my retreat

do not look like snow on the bamboo fence.

The paths of fishermen and woodcutters intertwine

and even after a hundred years I would not want to untangle them

Nor am I tired by memories of a past I never had....

Here his philosophy seems very close to Zen, lines composed almost as if by an ancient Chinese mountain hermit: "I do not think about the pines because they're me." It's a striking poem for its clarity of image and timelessness.

The more recent poems are less dependent on syntactical structures or philosophical, feeling increasingly "organic," almost if though the poet is seeking within the poem rather than directing, especially when he speaks of trying

"to escape from the ruinous evenings,

unendurable poverty and already manageable madness;

such is this place, which starts almost nowhere,

on almost roadless slopes and dry earth,

which like pebbles jingling in a dark purse

disturbs your peace, opens your invisible heart

and penetrates it like questions....

What can or cannot be remembered is a burning issue in these poems. Even the remembrance of "what is lost" is lost. He says, "Our death was torn from the pages of a fading book..." The temporal world is simultaneously known and unknown, and remembrance is an unreliable tool, even in the hands of a poet-historian.

Dato Barbakadze speaks with a distinct voice and rare vision in poems that invite contemplation more than dramatic reaction. If they sometimes feel a little cold at first reading, that may be because they carry the shivering realities of a life lived under harsh circumstances seen through eyes that did not turn away from tough questions. But always, poem by poem, there is within the poetry the warmth of real humanity and the brightness, the hungry intelligence of his song, fresh as new-fallen snow.

|

Dato Barbakadze - Introduction to Still Life with Snow by Sam Hamill Dato Barbakadze - Selections from Still Life with Snow Dato Barbakadze (born 7 February 1966) is a Georgian writer, essayist and translator. Biography Dato Barbakadze was born in Tbilisi. He studied philosophy and psychology in Tbilisi State University between 1984 and 1992 and holds a Masters degree in Philosophy. In 1992-1994 he pursued his post-graduate studies in the Department of Sociology at Tbilisi State University, but left a standard academic career to pursue independent projects in Georgian and German literature: he has followed a non-traditional academic path for the past twenty years (2010). In 1991 Dato Barbakadze founded a literary video-magazine Dato Barbakadze’s Magazine, which for two years was regularly performed at Tbilisi State University. He also founded the literary magazines Polilogue (1994, four issues) and ± Literature (1996, four issues). These publications featured many of the innovations of Georgian literature in the 1990s. From 1991 to 2001 Dato Barbakadze taught courses in logic, the history of philosophy, esthetics and introductory philosophy courses in several universities in Tbilisi. In 2002-2005 he lived in Germany where he pursued his literary interests and studied philosophy, ancient history and sociology at Westphalian Wilhelms-University of Münster. After returning to Tbilisi in 2005 Dato Barbakadze started the project XXth century Austrian Poetry, serving both as an editor and contributor. Dato Barbakadze has been a member of Die Kogge, an association of European writers, since 2007. His works have been translated into English, German, French and Russian. He lives in Tbilisi, Georgia. Published works (Georgian titles in parentheses) Poetry: Condolences to Fall (მივუსამძიმროთ შემოდგომას). Tbilisi 1991. Longing for Logic (ლოგიკის მონატრება). Tbilisi 1993, ISBN 99928-0-264-2. Putting the Question (საკითხის დასმა). Tbilisi 1994, ISBN 99928-0-265-0. One minute or One Life Before the Journey (გამგზავრებამდე ერთი წუთით ან ერთი სიცოცხლით ადრე). Tbilisi 1994, ISBN 99928-0-239-1. Roofbuilder (მხურავი). Tbilisi 1995, ISBN 99928-0-240-5. Negation of the Summary (შეჯამების უარყოფა). Tbilisi 1999, ISBN 99928-0-013-5. Essential Steps (არსებითი სვლები). Tbilisi 2001, ISBN 99928-0-125-5. The Songs of Lake Embankment (ტბის სანაპიროს სიმღერები). Tbilisi 2004, ISBN 99940-29-43-6. Poems 1984–2004 (ლექსები 1984-2004). Tbilisi 2008, ISBN 978-9941-0-0347-9. ars poetica. Tbilisi 2010, ISBN 978-9941-9115-4-5. In Defense of Memory (მეხსიერების დასაცავად). Tbilisi 2013, ISBN 978-9941-0-5981-0. From a Problematic Light (პრობლემური სინათლის გამო). Tbilisi 2015, ISBN 978-9941-0-8056-2. The window (სარკმელი). Tbilisi 2016, ISBN 978-9941-0-8444-7. Skeptical Etudes (სკეპტიკური ეტიუდები). Tbilisi 2019, ISBN 978-9941-8-0992-7. and so on (და ასე შემდეგ). Seven Haiku Wreaths. Tbilisi 2019, ISBN 978-9941-8-1470-9. Prose: Mutation (მუტაცია). Novel. Tbilisi 1993. The second heel of Achilles (აქილევსის მეორე ქუსლი). Novel. Tbilisi 2000, ISBN 99928-0-042-9. Short Prose 1990-2010 (მცირე პროზა 1990-2010). Tbilisi 2010, ISBN 978-9941-0-2441-2. Collected Essays: Poetry and Politics (პოეზია და პოლიტიკა). Tbilisi 1992. Resistances Head-On (შემხვედრი წინააღმდეგობები). Tbilisi 1994. Questions and Social Environment (კითხვები და სოციალური გარემო). Tbilisi 2000, ISBN 99928-0-041-0. Fragmentarium I. Tbilisi 2006, ISBN 978-99940-0-982-4. Fragmentarium II, III. Tbilisi 2008, ISBN 978-9941-0-0381-3. Fragmentarium IV. Tbilisi 2011, ISBN 978-9941-0-3279-0. Fragmentarium V, VI, VII. Tbilisi 2013, ISBN 978-9941-0-5264-4. Fragmentarium I-VII. Tbilisi 2013, ISBN 978-9941-0-5306-1. Fragmentarium VIII. Tbilisi 2015, ISBN 978-9941-0-7444-8. Reflektions on the German-language poetry of the XX. century. Tbilisi 2015, ISBN 978-9941-0-7527-8. Fragmentarium I-VIII. Tbilisi 2018, ISBN 978-9941-26-319-4. Letters on Literature: D/D (დ/დ). Tbilisi 2006, ISBN 99940-67-99-0. Unrealistically (არარეალურად). Tbilisi 2010, ISBN 978-9941-0-2442-9. Continuation (გაგრძელება). Tbilisi 2012, ISBN 978-9941-0-3977-5. Translations (into Georgian): From XX century German Poetry. Tbilisi 1992. Collection of European and American Poetry. Volume I. Tbilisi 1992. Collection of European and American Poetry. Volume II. Tbilisi 1993. Collection of European and American Poetry. Volume III. Tbilisi 2000, ISBN 99928-0-091-7. Hans Arp: Poems. Tbilisi 1992. Georg Trakl: Poems. Tbilisi 1999. Paul Celan: Poems. Tbilisi 2001. Hans Magnus Enzensberger: Poems. Tbilisi 2002, ISBN 99928-0-453-X. Brita Steinwendtner: Red Pool. Novel. Tbilisi 2005, ISBN 99940-29-75-4. Hans Magnus Enzensberger: Poems from The Language of the Country. Tbilisi 2007, ISBN 978-99940-0-803-2. XXth Century American Poets. Tbilisi 2008. Marianne Gruber: I do not know, if I am. Poems. Tbilisi 2008. ISBN 978-9941-12-258-2. Ernst Meister: Poems. Tbilisi 2009, ISBN 978-9941-9048-5-1. Translated due to circumstances 1989-2010. Tbilisi 2011, ISBN 978-9941-0-3278-3. Banesh Hoffmann: Albert Einstein. Biography. Tbilisi 2012, ISBN 978-9941-9221-9-0. Wladimir Pack, Andrej Baranjuk: Robert Fisher. Biography. Tbilisi 2012, ISBN 978-9941-9239-8-2. From 20. century German Poetry. Tbilisi 2012, ISBN 978-9941-0-4450-2. Hans Magnus Enzensberger: The Wolves Defended Against the Lambs. Poems. Tbilisi 2013, ISBN 978-9941-0-5212-5. Ernst Meister: Simple Creation. Poems. Tbilisi 2013, ISBN 978-9941-0-5214-9. Georg Trakl: DE PROFUNDIS. Selected Poems. Tbilisi 2014, ISBN 978-9941-0-6959-8. Michael Guttenbrunner: Holy Break. Poems. Tbilisi 2015, ISBN 978-9941-0-7368-7. Wilhelm Szabo: Simultaneity. Poems. Tbilisi 2015, ISBN 978-9941-0-7369-4. Günter Eich: Messages from the Rain. Poems. Tbilisi 2015, ISBN 978-9941-0-7651-0. Norbert Bolz: Who is Afraid of Philosophy? An essay. Tbilisi 2016, ISBN 978-9941-9469-5-0. The Secret of the Pearl. Jesidic Sacred Poetry. Tbilisi 2017, ISBN 978-9941-26-028-5. Translations 2014-2017. Tbilisi 2018, ISBN 978-9941-27-781-8. Helmuth A. Niederle: A Holy River. Poems. Tbilisi 2018, ISBN 978-9941-8-0148-8. Nikolaus Lenau: The Distance. Poems. Tbilisi 2018, ISBN 978-9941-26-339-2. Ilse Aichinger: Verschenkter Rat. poems. Tbilisi 2019, ISBN 978-9941-26-608-9. Friedrich Hebbel: The Nibelungs. Der gehörnte Siegfried. Siegfrieds Tod. Tbilisi 2020, ISBN 978-9941-26-686-7. Friedrich Nietzsche: Dionysian-Dithyrambs. Tbilisi 2021, ISBN 978-9941-8-3222-2. Translations 2018–2021. Tbilisi 2021, ISBN 978-9941-8-3652-7. Collected works Outcomes (შედეგები). Volume I. Mertskuli, Tbilisi 2014. ISBN 978-9941-0-7002-0. Outcomes (შედეგები). Volume II. Mertskuli, Tbilisi 2014. ISBN 978-9941-0-7003-7. Outcomes (შედეგები). Volume III. Mertskuli, Tbilisi 2014. ISBN 978-9941-0-7004-4. Outcomes (შედეგები). Volume IV. Mertskuli Verlag, Tbilisi 2018. ISBN 978-9941-8-0757-2. Outcomes (შედეგები). Volume V. Mertskuli, Tbilisi 2014. ISBN 978-9941-0-7113-3. Outcomes (შედეგები). Volume VI. Mertskuli, Tbilisi 2014. ISBN 978-9941-0-7027-3. Outcomes (შედეგები). Volume VII. Mertskuli, Tbilisi 2019. ISBN 978-9941-8-0993-4. Outcomes (შედეგები). Volume VIII. Mertskuli, Tbilisi 2014. ISBN 978-9941-0-7114-0. Outcomes (შედეგები). Volume IX. Mertskuli, Tbilisi 2014. ISBN 978-9941-0-7115-7. Works in another language In German Das Dreieck der Kraniche. Gedichte. Pop, Ludwigsburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-937139-38-8. Die Poetik der folgenden Sekunde. Poesie und Prosa. Drava, Klagenfurt 2008, ISBN 978-3-85435-557-1. Wesentliche Züge und zwölf andere Gedichte. Mischwesen, Neubiberg 2010, ISBN 3-938313-11-0. Die Leidenschaft der Märtyrer. SuKulTur, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-941592-35-3. Die Unmöglichkeit des Wortes. Theoretische Manifestationen. Pop, Ludwigsburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-86356-177-2. Meditation über den gefallenen Baum. Gedichte. Löcker, Wien 2016. ISBN 978-3-85409-766-2. Das Gebet und andere Gedichte. Pop, Ludwigsburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-86356-220-5. Wenn das Lied sich vom ermüdeten Körper befreit. Gedichte. Pop, Ludwigsburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-86356-241-0. Und so weiter. Sieben Haiku-Kränze. Deutsch von Maja Lisowski. Nachdichtung von Theo Breuer. Pop Verlag, Ludwigsburg 2021, ISBN 978-3-86356-322-6. In English Still Life With Snow and Other Poems. Bedouin Books, Port Townsend 2014, ISBN 978-0-983-2987-9-3. Passion of the Martyrs. Universali Publishing House, Tbilisi, Seattle 2017, ISBN 978-9941-22-970-1. In Russian Разное. Поэзия, проза, эссе. Издательство Meрцкули, Тбилиси 2016, ISBN 978-9941-0-8749-3. Publishing Project Austrian Poetry of the XXth Century (in Georgian) Volume I: Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Richard von Schaukal. Saari, Tbilisi 2006, ISBN 99940-29-94-0. Volume II: Georg Trakl. Saari, Tbilisi 2006, ISBN 99940-29-95-9. Volume III: Rainer Maria Rilke. Saari, Tbilisi 2007, ISBN 978-99940-60-30-6. Volume IV: Anton Wildgans, Albert Ehrenstein, Felix Braun. Saari, Tbilisi 2007, ISBN 978-99940-60-31-3. Volume V: Franz Werfel, Alexander Lernet-Holenia Polylogi, Tbilisi 2010, ISBN 978-9941-9048-4-4. Volume VI: Josef Weinheber. Polylogi, Tbilisi 2009, ISBN 978-9941-9048-3-7. Volume VII: Alma Johanna Koenig, Paula von Preradović, Erika Mitterer. Polylogi, Tbilisi 2010, ISBN 978-9941-9115-2-1. Volume IX: Theodor Kramer, Ernst Waldinger, Wilhelm Szabo. Samizdat, Tbilisi 2019, ISBN 978-9941-8-1138-8. Volume XI: Paul Celan. Samizdat, Tbilisi 2011, ISBN 978-9941-0-3978-2. Volume XII: Ingeborg Bachmann. Polylogi, Tbilisi 2010, ISBN 978-9941-9115-1-4. Volume XIII: Christine Lavant, Christine Busta. Polylogi, Tbilisi 2008, ISBN 978-9941-9048-4-4. Volume XIV: Hans Carl Artmann. Polylogi, Tbilisi 2008, ISBN 978-9941-9048-2-0. Volume XV: Ilse Aichinger, Friederike Mayröcker. Samizdat, Tbilisi 2020, ISBN 978-9941-8-2325-1. |

“Georgia is called Mother of the Saints, some of these have been inhabitants of this land, while others came among us from Time to time from foreign parts to testify to the revelation of our Lord Jesus Christ.”

(from – Passion of St. Abo).

The story of St. Nino, for all its fabulous embellishments, is built on a solid foundation of fact. History, archaeology and national tradition are unanimous in affirming that Iberia, as Eastern Georgia was then called, adopted Christianity as its state religion about A.D.330, in the time of Constantine the Great.

From the Georgian “Life of Saint Nino”

The Conversion of King Mirian, and of all Georgia with him

by our holy and blessed Mother, the Apostle Nino.

(Her festival is celebrated on January the 14th)

“This event caused a great sensation in Mtskheta and reached the ears of King Aderc himself. Everyone, including the princes and King Aderc, tried to take possession of the garment. But the monarch was overcome with fright and alarm when he found that he could not draw it from her arms. So firmly did she fold the garment to her breast that her brother Elioz buried it with her.

“Many years later the great-nephew of King Aderc, King Armazael, looked for the Tunic among the Jews, but failed to discover it or to learn anything about it, except that it was said to be buried near a cedar of Lebanon. But the family of Elioz knew that it was to the east of the city, by the bridge of the Magi.”

In the course of three years’ preaching she made many converts. Now there was a young boy belonging to a noble family who was dangerously ill, and his mother took him from door to door to see whether she could find anyone with the gift of healing to afford help in her trouble. But no one could heal the lad, and the doctors told the woman that her son could never be cured. This woman was a hardened pagan who detested the Christian faith and prevented other people from going to consult St. Nino.

“I have no authority to leave my humble tent Let the queen come here to my dwelling, and she will surely be healed by Christ’s power” There is no God besides Christ whom this slave girl preaches “

Then St. Nino went into Kakheti and converted the people. They received her teaching with joy and were baptized by Jacob the Priest. Then she went to Bodbe, where she was joined by the Queen of Kakheti with a great following of chiefs, warriors and women-slaves. She told them of Christ’s Holy Sacrament, and taught them the true faith with words of good cheer. She related the marvels which had been brought about by the living pillar, about which they had not yet heard. They welcomed St.Nino’s teaching with joy, and the queen was baptized with all her chiefs and handmaidens.

David Marshall Lang (6 May 1924 – 30 March 1991), was a Professor of Caucasian Studies, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. He was one of the most productive British scholars who specialized in Georgian history.

Selected bibliography

Lives and Legends of the Georgian Saints (New York: Crestwood, 1976)

The Last Years of the Georgian Monarchy, 1658-1832 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1957)

A Modern History of Georgia (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1962)

The Georgians (New York: Praeger, 1966)

The Peoples of the Hills: Ancient Ararat and Caucasus by Charles Allen Burney and D.M. Lang (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971)

georgianweb.com

The life of St. Gregory of Khandzta presents a number of links with that of St. Abo of Tiflis, the story of whose martyrdom we have related in the last chapter. Gregory, who was born in A.D. 759, was of almost exactly the same age as Abo; both of them were proteges’ of Duke Nerses of Georgia; both of them showed a predilection for the ascetic life. Their careers, however, were very different. St. Abo chose to offer lip his life as a martyr to the Christian faith; Gregory, on the other hand, preferred to leave the Arab zone of influence altogether, and help in Georgia’s national revival by mobilizing the spiritual forces of the nation against the Muslim overlords.

The district of Tao-Klarjeti in southwestern Georgia where Gregory settled with his followers presented at that time a picture of desolation and ruin. In reprisal for popular resistance to Arab rule, the Caliphs had sent expeditions to ravage the country; a cholera epidemic broke out soon afterwards.

In spite of these adverse conditions the time was ripe for St. Gregory’s ministry. Southwestern Georgia was the centre of patriotic resistance to Saracen rule. The movement was headed by the energetic Bagratid prince Ashot (780-826), who had quarrelled with his Arab suzerains and placed himself under the ages of the Byzantine emperor, from whom he received the imperial title of Kuropalates. Ashot had chosen Artanuj, on a tributary of the Chorokh, as his residence; he restored the ancient fort there and built a church dedicated to St. Peter and St. Paul. He was joined by thousands of refugees from the Arab zone of Georgia, who helped him to build up a new, national state. Ashot fostered the legend that his line, the Bagratids, traced their descent from King David of Israel.

The patriotic movement had much of the character of a crusade, and needed a militant religious leader. This role was ably filled by St. Gregory of Khandzta, who was as much a statesman as he was a dignitary of the Church. He became Archimandrite of twelve monasteries in Klarjeti, five of which were built or restored by him, and the others by his disciples. These formed a real monastic republic, with Gregory as their redoubtable and often despotic president. So strong did he become that he was able to interfere effectively in the private life of the ruling prince Ashot, and win for the monastic community a dominant position in public affairs.

Gregory lived to he a centenarian, dying on October 6th, 86r. His biography was written some ninety years after his death, in A.D. 951 by Giorgi Merchuli, in consultation with the prior of Khandzta, Gregory’s chief monastery. The work contains many realistic details of life in medieval Georgia; its many descriptions of geographical features moved its first editor, the late N. Y. Marr, to refer to it as a Georgian Baedeker. It is from Marr’s original edition of I 9 II that the following selected episodes are taken. Sub-titles have been added by the translator.

Introductory

The source of every good thing, namely Christ, the God of all creation, has implanted the root of wisdom in the character of true sages. Accordingly, you have the right to expect well-pondered wisdom from sages, while fools may be expected to listen in silence to the words of the wise. But nowadays, fools are philosophizing on their own account, and have imposed silence on the wise. They do not realize that as Solomon remarked, ‘Speech is silver, but silence is golden.’ For when the wise are overtaken by silence, then ‘their wisdom crieth in the streets,’ because their tongue does not utter idle words or backbiting, in so far as they are occupied in seeking out things of value and meditating on all forms of holiness and uprightness in virtue, and offering up prayers continually.

But since I have not the strength to pray without ceasing, and am beneath the level of idiots, my defects do not permit me to be silent. So rather than speak of any other thing, I have preferred to relate as well as I can for the benefit of my listeners the worthy life of those God-imbued men, our blessed father Gregory and his friends and disciples, as truthfully narrated by the saint’s pupils, and the pupils of his disciples.

Gregory’s early years

Gregory was the son of distinguished, noble and pious parents, and was brought up in the royal household of the great Duke Nerses by the care of the virtuous queen his wife, who had adopted him, for he was her nephew. From the womb he was dedicated by his mother to God’s service, like the prophet Samuel. Just like the Baptist, he grew up in fasting. From infancy, neither wine nor meat entered his lips, because he had set aside his soul as an abode for Christ; he put on the guise of monastic life, being free of youthful mischief and all human agitation. He dwelt by himself in his own quarters, so that people used to call him the Hermit.

His aptitude for learning was remarkable; he rapidly mastered the Psalms of David, studied all patristic literature in Georgian, learnt to read and write in many tongues, and could recite devotional books by heart. In addition, he made a thorough study of the wisdom of the philosophers of this world. Whenever he found there some excellent idea he absorbed it, but the evil he rejected. His perfect attainments became universally renowned; but he eschewed the externals of worldly wisdom, according to the words of the Apostle, ‘Has not God made foolish the wisdom of this world?’ In appearance he was tall, slim of figure, of goodly stature, in every way perfect in body and innocent in spirit.

Ordained a priest

Then the rulers, who had brought him up, as well as his estimable mother and the multitude of the people, wished to consecrate the blessed Gregory to the priesthood. Owing to his youth, the blessed one was overcome by misgivings. Then the wise princes said to him, ‘The honour of age, as Solomon says, consists not in longevity but in the intelligence of a man; a life of virtue constitutes mature years. Christ has given you excellent maturity of mind, so do not now disobey Him, but listen to Christ’s command and as a priest, serve that Eternal Priest who suffered for us and saved us all.’

So the blessed Gregory gave in to them and was ordained priest; and the multitude rejoiced as they received from his revered hands the Body and Blood of Christ.

Then the princes planned to make him a bishop, for he expounded the truth to all men like an angel of God, as it is written, ‘The priest’s lips should keep knowledge, and they should seek the law at his mouth; for he is the messenger of the Lord of hosts.’

Chooses the monastic life

When the blessed Gregory saw himself exalted in the flesh, his heart was very sorrowful, and he decided to flee secretly from his homeland in accordance with a divine summons which guided him like the patriarch Abraham. But while it was from a land of pagan tribes that God brought out Abraham, it was from a country of devout believers that He led Gregory away, in order that a light unquenchable might shine forth in the deserted wilderness.

To bring his virtuous design to fruition Gregory sought out good friends – his cousin Saba, who was called Saban, who restored and became bishop of Ishkhan; Theodore, builder and abbot of Nedzvi; and Christopher, builder and abbot of Kviriketi. Faith united these four into a partnership, and godly love strengthened their joint resolve.

Then they set forth joyfully on a road which they knew not; yet they were not plunged into bewilderment, because the Lord guided them on their way. And He led them first of all to Opiza. In Opiza there was a small group of brethren, who had collected there for the love of Christ, since a small church dedicated to St. John the Baptist was situated there. Their prior was called Abba George; he was the third prior of Opiza, Samuel and Andrew having passed away. Father Gregory and his companions spent two years at Opiza in arduous feats of monastic austerity, in accordance with the rules of the monks of that time.

Father Gregory, however, was yearning for a hermit’s life because he had heard of the angelic life of the anchorites in the solitary wilderness. Father Gregory visited them all and gained instruction in their excellent feats, from some of them in praying and fasting, from others in meekness and love, from others in kindness and freedom from malice, from others in poverty and the habit of lying on the ground or sleeping in a sitting position, from others in vigil and the silent cultivation of handicrafts, and other similar acts of virtue.

The building of Khandzta

At that time there lived in Khandzta an ancient hermit, a virtuous and holy man called Khuedios. This saintly man had a vision, not in his sleep, but in broad daylight. On that sacred spot where now is built the holy church of Khandzta, he saw a cloud of light in the form of a church standing a long time, and from the cloud there issued a powerful scent. And the saintly man heard a voice, ‘On this place a church will be built by the hands of Gregory the priest, the man of God, and the perfume of his prayers and those of his disciples will mount to God like a sweet incense.’ When he saw this vision he was very glad. Being accustomed to visions from God he started to wait for the holy man who had been announced.

Then our blessed father Gregory, guided by the Holy Spirit, arrived at Khandzta where the saintly hermit lived. They were very happy to meet one another, and offered up a prayer. At dawn, the hermit took St. Gregory to look round all the neighbourhood of Khandzta, and he took a great fancy to it. He said to the hermit, ‘I will go to Opiza and soon return with my brethren whom I have left there, so that they may come with me to receive spiritual benefit from your prayers. Arriving at Opiza, he told the brothers the glad news; so they promptly went to Father George, prior of Opiza, received blessings from him and all the community, and cheerfully came to Khandzta.

Then St. Gregory began to build Khandzta; and they consecrated a place apart and set to work to level the ground for cells, since the crags of Khandzta are the most precipitous of all the remote fastnesses of Klarjeti. They had great difficulty in preparing the site, as they had neither hatchets nor pickaxes nor any other tools. The monks of Opiza provided for all their bodily needs, since at that time there was no other fully constructed monastery in those parts besides Opiza. Nor were there any ordinary settlers with houses in that region; those parts of Klarjeti, Tao and Shavsheti had only lately been repopulated, so that there were only a few pioneers scattered in the woods round about.

The blessed father Gregory began by building a wooden church and then a hermitage for himself. The brethren had a little cell each, and a big room for a refectory. Every day their numbers increased: the Lord procured workers of the eleventh hour for the cultivation of that righteous vineyard.

In the meantime, the blessed hermit Khuedios had become very old and was nearing the hour of departure from the flesh. Our Holy Father Gregory and the brothers came to visit the hermit, and said to him, ‘Bless us, Holy Father, since now you are departing towards the Lord God!’ He replied, ‘May the God of peace, love and charity he with you in all things. Pray for me, holy fathers, for today I am going away to a strange abode before the awful throne of God.’ But they said, ‘You are no stranger to the abode of the holy angels, with whom you constantly rejoice in spirit before Christ.’ And so the blessed hermit found rest. Sweet was his sleep. And Father Gregory and the brethren bore away the body of him who had triumphed over the world, and buried it in a grave to the tune of sacred hymns; and they offered up thanks to Christ who grants victory to those who do His will.

Monastic austerities

In those early days of our blessed Father Gregory, the rules for his disciples were very severe. In their cells were small bedsteads with a bare minimum of bedding, and just a water-jug each. They had no other luxury in the way of eating or drinking apart from what they ate at the communal table-this was all they lived on. Many of them did not drink any wine at all, while those who did, partook of it in strict moderation. There were no chimneys in their cells because no fires were lit. Nor did they light candles at night. But the night time was spent in singing psalms and the day in reading books and praying.

During Lent, Father Gregory fed on just a little dried cabbage. His extra diet in ordinary times was a modicum of bread once a day, and water to the same amount. He never touched wine from his childhood days. God alone knows the countless merits of him and his disciples.

Gregory and Ashot the Kuropalates

At that period those regions were governed by the great and pious Bagratid ruler, Ashot Kuropalates, who permanently established the reign of his dynasty over the Georgians. Now there was a certain renowned gentleman in the service of Ashot Kuropalates; his name was Gabriel Dapanchuli, and his descendants are called Dapanchuli to this day. This gentleman was adorned with every perfection, with wealth, ripeness of judgment and a noble presence; he was renowned for success in all matters of business, as well as for his piety.

The noble Gabriel informed King Ashot the Kurapalates about the merits of Father Gregory and his building of a monastery in the desolate wilderness. When he heard this, the honorable Prince Ashot immediately wrote a letter with his own hand, and sent to Father Gregory a picked man from his retile with one of Gabriel’s servants. After he had read the prince’s polite letter of invitation, Father Gregory quickly went to see the ruler.

The Kuropalates said to Father Gregory, ‘To the kings of Israel God sent prophets from time to time to bring them glory and defend the law. In the same way God has made you eminent in our time, to bring glory to the Christians and constantly intercede for us before Christ.’

He replied, ‘Monarch, you who are called the son of the divinely anointed prophet David, may Christ confirm you in the inheritance of David’s kingdom and virtues. Therefore I make this pronouncement: “May the rule of your children and their seed never be removed from this land for all time, but may they stand firmer than immovable rocks and eternal mountains and be glorified for ever!”

After this the man who had been sent as messenger gave an enthusiastic account of Khandzta, declaring, ‘This solitary spot is excellent for the warmth of the sun and the mildness of the air all around. It has a free flowing spring, beautifully cool and pleasant. There are countless groves of trees, and as much in the way of crops as one can expect to grow in the wilderness, but there are no fields for harvest or for hay. Nor is it possible for any to exist there on the sharp and craggy peaks of the Ghado mountains.’

When he heard this, the renowned Kuropalates granted them fine estates, including that of Shatberd as a farm and country resort for Khandzta. Each of the prince’s three noble sons, Adarnerse, Bagrat and Guaram, also provided generously for the needs of the monastery.

During the saint’s lifetime, the sovereign Ashot Kuropalates conquered many lands. He built the castle of Artanuj as a residence for the queen his consort, and lived with her happily for many years. But the devil led the monarch astray. He introduced into the castle a concubine with whom he committed adultery, for the demon of love had greatly excited him.

When St. Gregory heard of this soul-destroying conduct he was greatly upset and began personally to rebuke the sovereign. The ruler promised to put a stop to his sinful ways, but was not strong enough to keep his word, as he was a slave to his passion.

The blessed Gregory bided his time. One fine day, when Ashot was in a far country, he set out from Shatberd to Artanuj; arriving towards evening in front of the castle, he sent a man to see the woman we have mentioned and ask for foot’. She was very glad, and gave various provisions for the holy man and his disciples. When morning came, he again sent the man to her, with a request for a personal meeting.

Even more glad, she promptly came out to see the saint, accompanied by two maids, in order to receive the holy man’s blessing. But he did not give it to her and ordered her to sit down a little way off. The disciples withdrew at a glance from their mentor, as well as the maids, for everyone stood in awe of the saint. Then the blessed Gregory said to her, ‘Wretched creature! Why have you come between husband and wife ensuring perdition for yourself through this grievous sin of y ours which enslaves you to the devil, and frivolously offering yourself as a temptation for the great sovereign?” She said tearfully, ‘Holy man of God, I have no power over myself, because the prince is deeply in love with me, anti now I do not know what to do. I am extremely distressed by what you have said.’ The saint continued, ‘My child, obey fully my words, which are those of a pious man, and I pledge myself before Christ that He will forgive you all your sins.’ She answered, ‘Holy Father, I am in your hands. Intercede on behalf of my soul.’

Only then did he grant her his blessing; then he gave her a lace from his sandals to gird herself with and said to her, ‘My child, today is the salvation of your soul; I will take you to the blessed abbess Mother Fevronia.’ This cheered her very much. Then Gregory told the maids to go back home into the castle, and said to the woman, ‘My child, we must be on our way. Go in front of us.’ And so he brought her to the convent of Mere. The blessed abbess’ consent had already been given beforehand, and he confided her to Fevronia’s care with the words, ‘Look after her, and take every precaution when the Kuropalates starts searching for her. You see how chastened is her spirit.’ She said, ‘Christ will take good care of His servant, whom He has found through you, worthy Father!’

Meanwhile the Kuropalates appeared at the castle and asked after the woman. As he could not find her, he was indignant, because he had an inkling of what had happened, and promptly went to Mere. After receiving Mother Feveonia’s blessing, the prince engaged her in conversation: ‘Do you know, Mother, why I have come here now?’ ‘The Lord knows,’ she replied, ‘why you have come.’ ‘I have come,’ he said, ‘because Father Gregory, so it seems, has brought here the woman who is stewardess of our house. All our property was in her custody, and we have discovered a serious deficit in our treasury. So kindly command her to attend at the castle; she can hand over everything according to the account-book, and then she may return to you or do as she likes.’

Fevronia retorted sharply, ‘Beware of exciting my indignation against sinful people who commit wicked crimes.

When he heard these words, the prince was confused by the justice of her reproach and stood for a long while in shamed silence, as if struck dumb. At length the downcast Kuropalates said in a rueful voice, ‘Happy is the man who is no longer alive.’ Then he got up quickly to leave. The blessed Fevronia, who was kind-hearted, tried to persuade him to stay for some refreshment, but he would not consent. The desire for carnal passion had quitted him, and he had become conscious of the shamefulness of his conduct. In spirit he rejoiced because wisdom had conquered pernicious weakness; in a pure heart he revered the blessed ones who had bestowed on his soul the crown of eternal salvation.

Gregory visits Constantinople

Father Gregory said to himself, ‘Since the brethren in my monastery are superior in virtue to the monks of this age, a set of ecclesiastical rules ought to be instituted for my church, so that it may not be exposed to criticism from expert theologians.’ For this purpose he made plans to go to the treasury of Christ, the second Jerusalem, which is Constantinople, to visit all the remarkable holy places of Greece and pray there.

Just then, he found that one of his friends was making a trip to Jerusalem, so he asked him to write down the monastic rules of St. Savva and send them to him.

Then he appointed deputies to look after the brethren and took leave of them, promising to return soon. He took with him his cousin Saba and another disciple of his and set off for Greece. Arriving at Constantinople, he made obeisance to the Wood of Life and all the other holy relics, and joyfully went round to pray at all the sacred shrines ; for he knew many languages and was versed in godly knowledge. Some of the things he saw served him as a model of excellent; while others provided a warning against evil. In this way his heart was filled with the ineffable riches of the New Testament. Cheered by spiritual grace, they set off on their homeward way.

When they reached Tao they heard from the local folk that Ashot Kuropalates had been assassinated, and that his sons were reigning in his stead. Then they were overcome with grief at the fate of the god-fearing monarch, and tearfully offered up prayers for their dead king. After this they prayed for his sons, the noble princes, that the Lord might preserve them and prolong their days in glory and pious works.

And so they arrived at Khandzta, their own monastery, bringing with them relics of the saints, holy icons and many other sacred objects. They found all the brothers well and in good spirits, and were glad now that the grace of our Savior had once more reunited His servants. After a few days Gregory sent Saba to Ishkhan and gave him two of his disciples. He himself directed the spiritual life of Khandzta in accordance with God’s will.

Afterwards, the man who had been to Jerusalem returned, and handed over a document containing the monastic rules of St. Savva. The blessed Gregory then laid down regulations for his own church and monastery, as selected and compiled from those in force at all the holy places.

Relations between Church and State

By the will of God, and with the consent of his brothers and by command of the Greek Emperor, the Kuropalates Bagrat succeeded his father, the Kuropalates Ashot, for he was divinely appointed to exercise authority; and both his brothers, the noble prince Adarnerse, the elder and Guaram, the younger, submitted to him in divine brotherly love. The realm of these three princely brothers grew through Christ’s virtue and grace, so that they conquered many lands by the sword and drove out the children of the Saracens.

At this time, Gregory’s heart moved him to remember Saba of lshkhan, and he informed the pious Kuropalates of all his earlier career. When Bagrat heard about this he was glad and quickly wrote a letter and sent worthy envoys to extend him an honorable invitation, But these envoys returned and returned to the Kuropalates, ‘The man of God declines to come here.’ Then the prince said to Gregory, ‘It was stupid of me not to entrust the writing of that letter to you. Now please write to him in suitable terms.’ The blessed Saba obeyed the prince’s second summons, the more especially through respect for Father Gregory’s letter. The prince came out to meet him and greeted him with respect, and Saba blessed him.

When they had sat down the prince said to Saba, ‘Obedience is due to the sovereign. Why did not you come at my first summons, Holy Father ?’

He replied, ‘Noble King, you are lord of the earth, but Christ is lord of the heavens, the earth, and the underworld ; you are lord of this nation, but Christ is Lord of all man that are born; you are king of this transitory time, but Christ is King eternal. He remains perfect and unchangeable, timeless, without beginning or end, King of angels and of men, and His words are to be heeded more than yours. Christ declared: No man can serve two masters. But now I have come before you in obedience to the word of our brother and pastor Gregory.’

The prince answered: ‘Your words are just, holy man. But it is better to illumine many souls by setting oneself up like a lighted candle on a candlestick. Christ said to His disciples: Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven.’

After this the prince went to Ishkhan, accompanied by the blessed fathers Gregory and Saba; and the prince liked that place very much. But why prolong our account? By God’s will Saba became bishop of Ishkhan, with authority over the see and the cathedral church originally built by the blessed Nerses, Catholicos of Armenia, which had been left in desolate widowhood for many years. Now it was built again by the blessed Saba with the material aid of those pious princes, and Ishkhan began to flourish perpetually and for all time.

Distinguished careers of Gregory’s disciples

Let us recall Gregory’s worthy pupils Arsen and Ephraim. It pleased God to make them both bishops, each having his own spiritual flock. Many years before Arsen, the great Ephraim became bishop of Adsqur and primate of Samtskhe. Later the great Arsen became Catholicos-Patriarch in the cathedral church of Mtskheta, where the Tunic of our Lord is preserved. Having been brought up together they were very fond of one another.

The great Ephraim became a great benefactor to our land. Earlier, the Catholicos-Patriarchs of the East used to bring the holy chrism for their consecration from Jerusalem. But Ephraim instituted anointment with holy chrism prepared in Georgia, by glad consent and authorization of the Patriarch of Jerusalem. – Georgia is reckoned to consist of those spacious lands in which church services are celebrated and all prayers said in the Georgian tongue. Only the Kyrie-eleison, which means ‘Lord, have mercy,’ or ‘Lord be merciful to us” is pronounced in Greek.

The blessed Ephraim was bishop for forty years; he perceived the secret deeds of men as if they had been public, and by his word cured deadly diseases in a twinking. By a word also he could smite the unrighteous with death many such miracles he used to perform. He passed away at a great age, filled with divine grace.

In Father Gregory’s time the worthy bishop Zacharias accomplished the following marvels: –

Near the monastery of Tbeti a fearsome crag was trembling on the edge of the cliff, and the monks fled from their dwellings in terror. Zacharias stayed confidently, and said to them: ‘Tomorrow you will see that crag lying in a place quite harmless to us.’ And so it turned out. The fathers did not notice its trembling any more, and next day it was lying motionless on a spot which they had not expected, just as the saint had said; and they glorified Christ.

This same Zacharias was sitting one autumn day in Tbeti, under his own ripe grapevines, at which a black-bird was persistently pecking. So he made the sign of the cross over it, and it immediately fell dead. Once more he made the sign of the cross, and the blackbird revived and flew off to its family.

An evil plot frustrated

Among this holy wheat there grew a noxious weed in the shape of a deacon who had been educated in Tiflis by the Amir Sahak, son of Ismail, and been sent as his representative to Ashot Kuropalates When he saw that the bishop of Anchi was dead this evil man, whose name was Tskir, petitioned Ashot through the Amir Sahak for the episcopal see of Anchi. When as a result of God’s forbearance Tskir had forcibly taken possession of Anchi, he heaped evil upon evil to an extent which cannot be set down in this book.

He was often reproached for his irregular conduct by the pioneer hermit fathers of Klarjeti and all the Orthodox bishops, and most of all by Father Gregory, archimandrite of those famed retreats. But Tskir secretly summoned a certain layman of Anchi, a poor lewd fellow, but a powerful marksman, and promised to give him three bushels of millet and five goats, and sent him to Khandzta to kill Father Gregory. On the way, this man found out from someone that Gregory was at the country estate belonging to Khandzta anti would be returning home that very day. So he went to lie in ambush in the wood of Khandzta, carrying his bow already strung.

Meanwhile our blessed Father Gregory was walking down by himself from the country estate towards Khandzta. Then the wretched villain saw a great apparition all around the saint: he was surmounted by a pillar of light shining brilliantly and extending up to heaven. On his head was a cross giving out radiance all round, like a rainbow in showery weather. Seeing this marvel, the man was seized with intense fear; as if the sinews of his arms had been dissolved, he fell on the ground in terror.

The blessed Gregory said to him, ‘Miserable wretch, carry out the orders of him that sent you. For a trifling reward you planned to kill a simple monk. Is it not a fact that you foolishly came to murder roe for three bushels of millet and five goats I’ Then that man broke down and implored him, ‘Have pity on your murderer, O man of God!’ The saint mercifully made the sign of the cross over him, and cured him of die many bodily ailments to which lie was subject, and sent him home in good spirits.

When the man told Tskir about all this he became more and more blind with rage. So he assembled the people of Anchi and sent them to destroy Khandzta, where they arrived at dawn. When Tskir had sent this mob to Khandzta he himself went off to Korta to fetch some valuables lie had deposited there.

As they were taking a meal on the way he dozed off and had a terrible vision in which his wicked deeds were unmasked, and especially the injuries which he had inflicted on the men of Khandzta. A certain pious priest of Anchi was then with him, and the Lord revealed to this man that an evil end awaited Tskir; so the priest sent a pupil of his to Khandzta to bring advance news of the death of Tskir.

When the pupil arrived he said, ‘Do not venture to ruin noble Khandzta, for its destroyer is dead.’ Then the people were glad, the fathers entertained them, and they went gaily home glorifying God. As for Tskir, when he reached Korta, he expired on the spot, and they buried him there until the Second Coming of our Lord.

Death of St. Gregory

This blessed man of God, Father Gregory, repository of Christ’s will and worker of famous miracles, lived to be exceedingly old, and reached the age of one hundred and two. But the colour of his face never changed nor was his eyesight dimmed : he remained vigorous in body and suffered no infirmity until his death, for he was fortified by the strength of Christ. He was very fond of working, not only in praying and fasting, but also at manual labour, in accordance with Paul’s words, ‘If any would not work, neither should he eat.’ He enjoyed offering hospitality and looking after the poor. He had appointed abbots to look after his various monasteries; if any exceptional problem cropped up, they consulted him about it for the sake of his God-given wisdom.

In the blessed Gregory’s heart there arose the desire to take leave of the flesh and depart towards God. The Lord told him that his wish would be fulfilled, as David said, ‘He will fulfil the desire of them that fear Him: He also will hear their cry, and will save them.’ Then he instructed the brothers to prepare candles for distribution to all the hermitages in the country round, and told them on what day they were to be lit and prayers offered up for him.

Afterwards be said to the brethren, who lived in Khandzta, ‘My sons, observe the precepts which you first heard from me for the salvation of your souls, and remember me always. If in the presence of Christ I find courage to speak, then His generous blessings will not cease to shower upon you in this world and the next. When death has parted me from you, remember me always in your prayers and commemorations, and watch over the scene of my earthly pilgrimage. Until the day of judgment, my flesh will turn to dust, hut may God receive my spirit.’

While the blessed Gregory was speaking these words he appeared as lit up with the ineffable radiance of Christ; and he rejoiced with supreme happiness, and made the sign of the cross over his monastery, and uttered an everlasting blessing upon his disciples ‘O Christ, our Lord, Thou didst suffer and wast tempted, and art powerful to help those who are sore beset by the wiles of the devil, for Thou art the supporter of Christian folk. O Lord, protect with Thy right hand those who set their hopes upon Thy name, and deliver them from the evil one, and grant them joy eternal. As for me, Thy servant, grant me life in Thy kingdom and remember me mercifully in Thine almighty power.’ So he committed his soul to the Lord and was united with the company of angels.

The death of our blessed Father Gregory occurred in the 81st year of the Paschal Cycle (A.D. 861). His biography was written ninety years after his passing, when 6554 years had elapsed since the Creation; Agathon was Patriarch in Jerusalem, Michael was Catholicos in Mtskheta, and Ashot Kuropalates, son of King Adarnerse, was prince of the Georgians. This biography of the blessed Gregory was written at Khandzta by Giorgi Merchuli, through the joint zeal of the abbot of Khandzta and his brother John. May Christ write them down in the book of living souls, and show His mercy in full to all believers, that they may appreciate the generosity of God in this world and the next.

In a church one reader is enough, whether there be few listeners or many. In the same way it is enough for one to bless, whether one or many are to he blessed; for inexhaustible are Christ’s good gifts to us, and the saints’ interceding grace.

georgianweb.com